Saturday, December 28, 2013

Good Infographics give Interesting Perspective

How to Be an Educated Consumer of Infographics: David Byrne on the Art-Science of Visual Storytelling

by Maria Popova

Cultivating the ability to experience the “geeky rapture” of metaphorical thinking and pattern recognition.

As an appreciator of the art of visual storytelling by way of good information graphics

— an art especially endangered in this golden age of bad infographics

served as linkbait — I was thrilled and honored to be on the advisory

“Brain Trust” for a project by Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist, New Yorker writer, and Scientific American neuroscience blog editor Gareth Cook,

who has set out to highlight the very best infographics produced each

year, online and off. (Disclaimer for the naturally cynical: No money

changed hands.) The Best American Infographics 2013 (public library)

is now out, featuring the finest examples from the past year — spanning

everything from happiness to sports to space to gender politics, and

including a contribution by friend-of-Brain Pickings Wendy MacNaughton — with an introduction by none other than David Byrne. Accompanying each image is an artist statement that explores the data, the choice of visual representation, and why it works.

As an appreciator of the art of visual storytelling by way of good information graphics

— an art especially endangered in this golden age of bad infographics

served as linkbait — I was thrilled and honored to be on the advisory

“Brain Trust” for a project by Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist, New Yorker writer, and Scientific American neuroscience blog editor Gareth Cook,

who has set out to highlight the very best infographics produced each

year, online and off. (Disclaimer for the naturally cynical: No money

changed hands.) The Best American Infographics 2013 (public library)

is now out, featuring the finest examples from the past year — spanning

everything from happiness to sports to space to gender politics, and

including a contribution by friend-of-Brain Pickings Wendy MacNaughton — with an introduction by none other than David Byrne. Accompanying each image is an artist statement that explores the data, the choice of visual representation, and why it works.Byrne, who knows a thing or two about creativity and has himself produced some delightfully existential infographics, writes:

The very best [infographics] engender and facilitate an insight by visual means — allow us to grasp some relationship quickly and easily that otherwise would take many pages and illustrations and tables to convey. Insight seems to happen most often when data sets are crossed in the design of the piece — when we can quickly see the effects on something over time, for example, or view how factors like income, race, geography, or diet might affect other data. When that happens, there’s an instant “Aha!”…Byrne addresses the healthy skepticism many of us harbor towards the universal potency of infographics, reminding us that the medium is not the message — the message is the message:

A good infographic … is — again — elegant, efficient, and accurate. But do they matter? Are infographics just things to liven up a dull page of type or the front page of USA Today? Well, yes, they do matter. We know that charts and figures can be used to support almost any argument. . . . Bad infographics are deadly!And, indeed, at the heart of the aspiration to cultivate a kind of visual literacy so critical for modern communication. Here are a few favorite pieces from the book that embody that ideal of intelligent elegance and beautiful revelation of truth:

One would hope that we could educate ourselves to be able to spot the evil infographics that are being used to manipulate us, or that are being used to hide important patterns and information. Ideally, an educated consumer of infographics might develop some sort of infographic bullshit detector that would beep when told how the trickle-down economic effect justifies fracking, for example. It’s not easy, as one can be seduced relatively easily by colors, diagrams and funny writing.

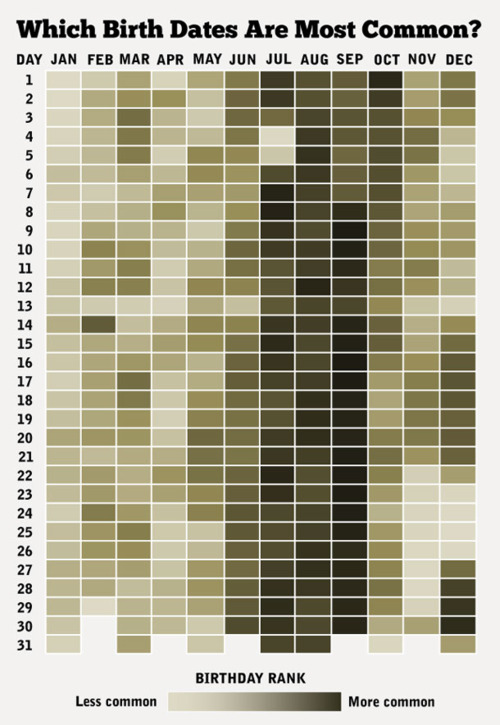

The days of the year, ranked by the number of babies born on each day in the United States (Matt Stiles, NPR data journalist)

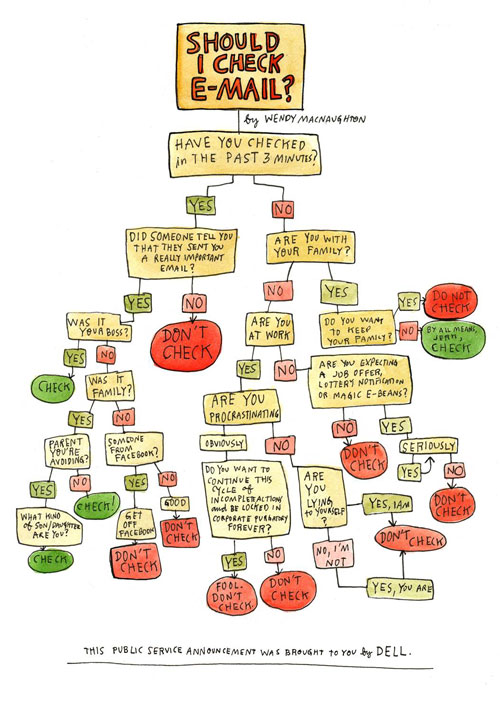

Flowcharts [are] a form of poetry. And poetry is its own reward.Indeed, flowcharts have a singular way of living at the intersection of the pragmatic and the existential:

A handy flowchart to help you decide if you should check your email. (Wendy MacNaughton, independent illustrator, for Forbes)

Just ask yourself one question. (Gustavo Vieira Dias, creative director of DDB Tribal Vienna)

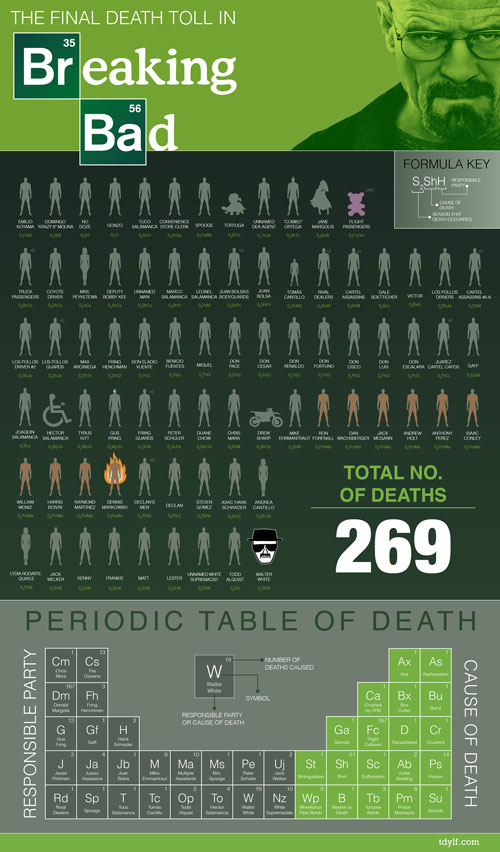

All of the deaths in the first fifty-four episodes of AMC's ‘Breaking Bad,’ with each deceased character represented by a faux chemical formula indicating when he or she died, how they died, and who killed them. (John D. LaRue)

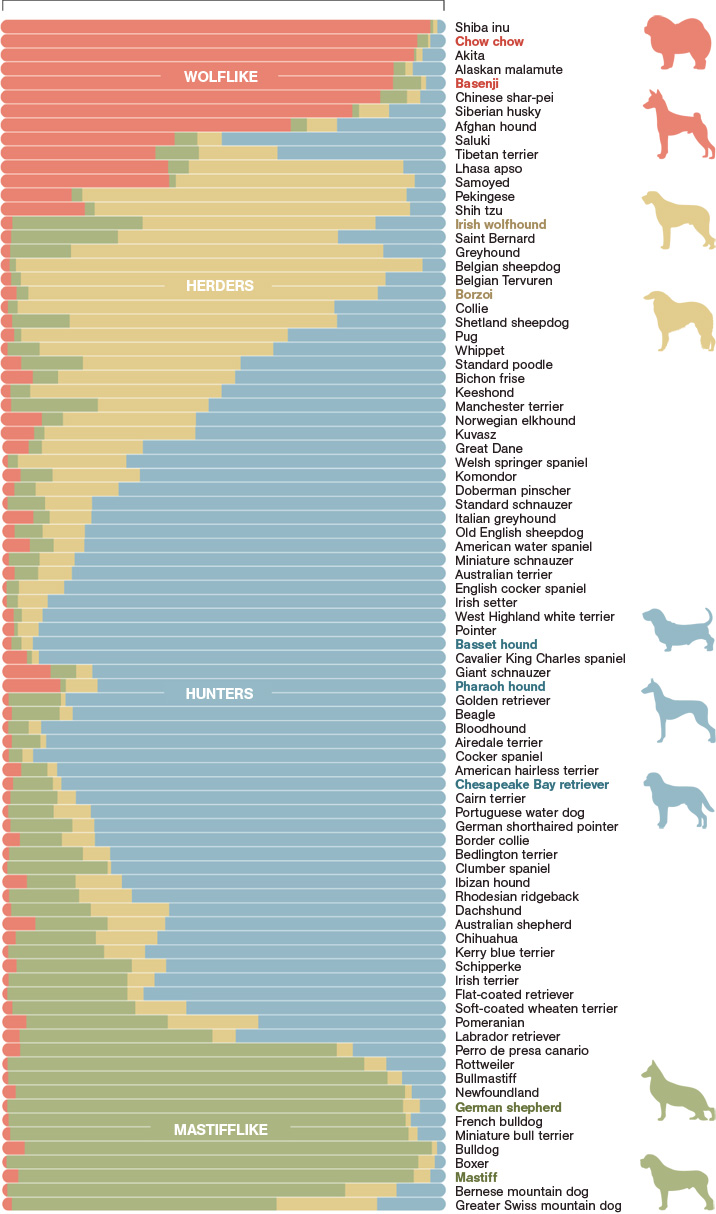

Analyzing the DNA of 85 dog breeds, scientists found that genetic similarities clustered them into four broad categories. The groupings reveal how breeders have recombined ancestral stock to create new breeds; a few still carry many wolflike genes. Researchers named the groups for a distinguishing trait in the breeds dominating the clusters, though not every dog necessarily shows that trait. The length of the colored bars in a breed’s genetic profile shows how much of the dog’s DNA falls into each category. (John Tomanio, senior graphics editor, National Geographic)

‘Flow map’ of travel in New York City derived from the locations of tweets tagged with the locations of their senders. The starting and ending points of each trip come from a pair of geotagged tweets by the same person, and the path in between is an estimate, routed along the densest corridor of other people's geotagged tweets. (Eric Fischer, artist in residence at the Exploratorium in San Francisco)

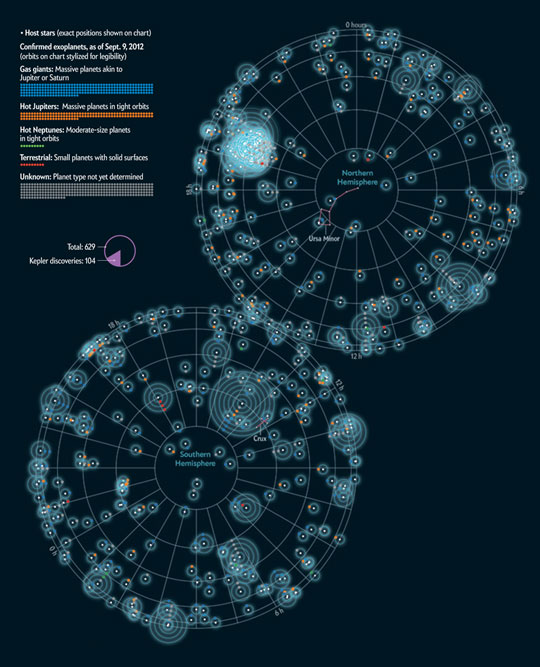

All of the planets discovered outside the Solar System. (Jan Willem Tulp, freelance information designer, for Scientific American)

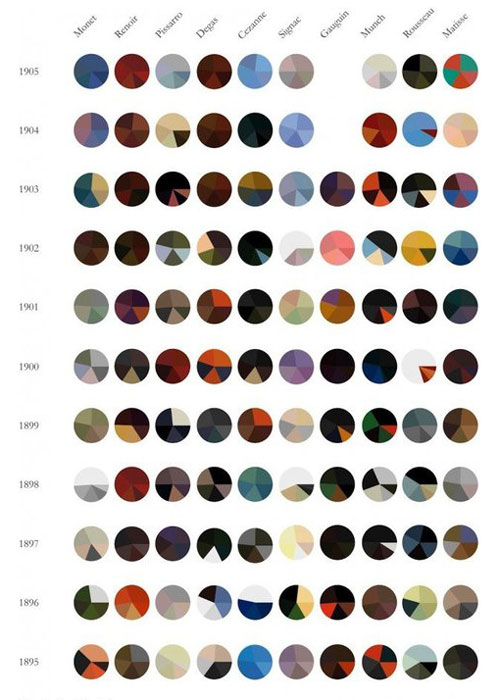

A revolution in color over ten extraordinary years in art history. Each pie chart represents an individual painting, with the five most prominent colors shown proportionally. (Arthur Buxton)

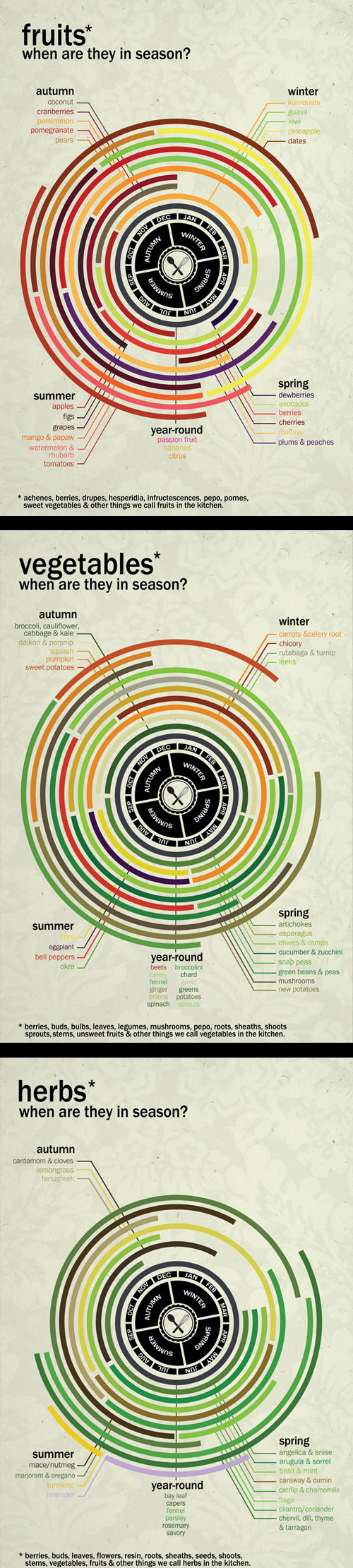

The availability of produce in the northern hemisphere by month and season. (Russell van Kraayenburg)

We have an inbuilt ability to manipulate visual metaphors in ways we cannot do with the things and concepts they stand for — to use them as malleable, conceptual Tetris blocks or modeling clay that we can more easily squeeze, stack, and reorder. And then — whammo! — a pattern emerges, and we’ve arrived someplace we would never have gotten by any other means.Complement The Best American Infographics 2013 with Nathan Yau’s indispensable guide to telling stories with data and Taschen’s scrumptious showcase of the best information graphics from around the w

Monday, December 16, 2013

Thursday, December 05, 2013

The Temple Conolly Review of Avakai Biryani

Avakai Biryani

Filed under: Tollywood by Temple Connolly — 6 Comments

October 15, 2010

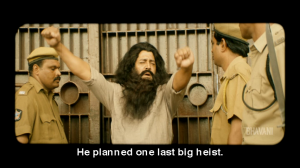

Akbar Kalam is a Muslim, an auto driver, a student and an orphan. He is caught between worlds and striving to make his way. He lives in a charity cottage, works for Master-ji the local big-wig, and dreams of getting his B.Comm despite failing his exams several times. His exam record is a running joke in Devarakonda.

Spirited graduate Lakshmi (Bindhu Madhavi) and her Brahmin family arrive in Devarakonda needing to start over after losing their fortune. Lakshmi starts making and selling her signature avakai and tries to get her father motivated to get back on his feet.

They both belong and yet they don’t, both making the best of what they have, and so a friendship grows. Lakshmi agrees to tutor Akbar and he helps her fend off unwanted attention from Babar – a leader in the Muslim community and a man with a predilection for satin pajamas. I seriously doubt Akbar was failing only because of his English skills, but Lakshmi doesn’t give up on him as quickly as I would have!

The handling of diversity in the Devarakonda population seemed to me to be very well done. I don’t have the expertise to comment on the reality of this portrayal but can say that as a narrative device it works extremely well. While religion does draw a line through the community, it is depicted as one among many divisions in this village. There are lines of caste, creed, financial status, education and of relationships. Characters cross these lines and back again as the business of making a living and getting the chores done is uppermost and there are few moments of speechifying. The lines of division become much sharper when marriage is in question, and that underpins much of the story.

We see where this is heading a long time before Lakshmi and particularly Akbar seem to. I have my doubts as to how long a boy and girl can hide any “friendship” in a small community, but their roaming around does give Kuruvilla the chance to show the beauty of rural Andhra Pradesh. The growing relationship seems natural and unforced and is not based on any love-at-first-sight or stalking. He calls her Avakai (or as my subtitles have it, Pickles), referring to her identity but also to her hopes for building a future. Their love grows from knowing and valuing each other.

The obligatory spanner in the works comes from the ongoing tension with Babar which is fuelled by testosterone, religion and politics. Babar tries to use religion as a lever to force Akbar to back down but fails as the hero decides to do what’s right for the whole village in a scene with shades of SRK in Swades.

Threats are made, scuffles take place and things boil over between the two men. There is only one way for honour to be satisfied. By an auto race around the village! I know some people rolled their eyes at this episode but it rang true to me. I just rolled my eyes at the sheer stupidity and very boyish behaviour. Oh and it allowed Kamal Kamaraju to get his shirt off, which I suspect is a legal obligation for any Telugu film hero. And there was an explosion, which may also be a compulsory element as well as a machete flourish.

Having established his right to stay in the village, managed a scheme to bring mains water to Devarakonda and finally passed his exams, Akbar has one last obstacle – getting Lakshmi. Despite acknowledging his help and decency towards them all, her family refuse to consider him as a suitor because of his religion and because of his limited prospects. Akbar and Lakshmi simply go their separate ways. Her family pressure is too much to withstand, and he has no family to offer them shelter or support.

This is a total spoiler so stop now if you don’t want to know how it all ends.

Akbar throws himself into work, builds on his success in politics and becomes a respected member of the local council. Two years on, Lakshmi’s father hears him speak at a political meeting and apparently undergoes a change of heart on hearing successful Akbar still speak of Lakshmi with feeling. She sends Akbar a jar of pickles with a note asking him to meet her. He looks radiant with joy as he realises the note is from Lakshmi and she is doing well.

They meet, she pretends not to mind his dodgy moustache, and then hands him a wedding card. There are tears on both sides before he sees the card is for their own wedding and that’s it. Happy ever after time. I expected a bit of anger from Akbar at this cruel trick but I think it’s already clear who really wears the pants in this relationship.

Surprisingly I don’t think this ending was either a cop out or disgraceful behaviour by her dad. Neither Akbar nor Lakshmi had the resources to throw family aside and go it alone. I can imagine it would be hard to marry off an opinionated educated girl especially if people began to talk about her relationship with the Muslim boy. She may not have had many takers after all. And why wouldn’t career success influence a father who has experienced losing everything and seeing his family suffer? Anyway I liked the resolution. No fireworks, just happiness and relief. I really liked that the girl was fully involved in choosing her own path and went in with eyes wide open.

The cinematography is beautiful. The colours are lush and welcoming; the village is dilapidated and picturesque. Kuruvilla paces the story well and doesn’t resort to the predictable speeches and characters. Both leads look good but not too glamorous. Their dancing is not brilliant but it seems entirely suited to the characters so their emotions were the real focus, not fancy footwork. The music blends with the story and the songs are used well, with matching choreography from Prem Rakshith

All the support cast are effective and resist descending into total caricatures. The actors who play Akbar’s best friends are great fun, particularly Praneeth as Sondu who is the embodiment of the fiery spirited party boy that loves his booze, good times and his mates.

I have said before that romance is my least favourite genre. Often I find the plots too silly and the characters poorly acted or insufficiently interesting for me to care about how they are going to navigate the ridiculous story. Avakai Biryani is a successful film for me. It has substance and some thoughtful commentary in addition to charm and pretty visuals. The leads give good solid performances, and the supporting performers are excellent. I give this 4 stars! Temple (Heather will post a film review soon. Don’t panic!)

Wednesday, December 04, 2013

Avakai Biryani: Filmowe zaduszki AD 2013: 'Ko Ante Koti' & 'Memori...

Avakai Biryani: Filmowe zaduszki AD 2013: 'Ko Ante Koti' & 'Memori...: Jak to już stało się moją doroczną tradycją, w listopadzie po raz kolejny przystąpiłam do filmowych 'wypominek', czyli ekranowych s...

On Malayalam Cinema - Nisha Susan

The Pot that Broke Below a Hundred Other Pots

If you have the option of picking from among half a dozen cinematic traditions, why would anyone choose to look for romance in Malayalam cinema – the most determinedly unromantic of them all?

By Nisha Susan | Grist Media – Mon 2 Dec, 2013

Towards the middle of Aaraam Thampuran, a 1997 movie with Malayali actor Mohanlal in the lead, the hostile villagers are steadily awakened to the true ‘noble’ roots of the bad man who has bought the big house. The villagers – and the audience – are given broad hints that he isn’t just the goonda from Bombay they thought he was. It is in the nature of the movies the Malayalam industry was making in the late 1990s that Jagan (Mohanlal) was revealed to be not just a secret aristocrat; he was a secret aristocrat from the village who has now returned to his rightful place. The ‘Lost Heir’ is not a new trope, but hoary as it is, it can still be satisfying.

Unfortunately, what was memorable for me about the Lost Heir in this movie was something that happens in the middle of the film. Someone from the city comes to meet Jagan for prosaic business. The moment he sees Jagan the man is wreathed in confused smiles. “Aren’t you the Jagan who ran an art journal in Delhi?” Mohanlal the actor tries to look modest and yet cosmopolitan but looks like he is suppressing giggles instead. The establishing of Jagan the violent thug as a Delhi gallery owner, a classical musician in Gwalior, a jet-setting aesthete, is done with this swift exchange, followed by the arrival of his long-term city girlfriend who offers to cheer him up by taking him to any of his favourite places. “London? Paris? Vienna?” she trills alongside being ‘chulbuli’ – the pan-India cinematic mutation of female vivaciousness, which is usually represented as chihuahua on speed.

As an 18-year-old, Aaraam Thampuran made me wince for days. “Ningal Alle Delhi yile aaa art journal…? (Aren’t you…? The one who ran the art journal in Delhi?)” over the years became my shorthand for unconvincing, name-dropping arty characters in movies. It embarrassed me deeply. (Perversely, Suresh Gopi, hero of Lelam – also from 1997 – resorting to Yiddish in the middle of a trademark tirade against the villains, ‘You schmuck’, only made me fall about laughing.)

Over the years, I’ve also become a little grudging of the long explanation (such as the one in the above paragraph) I must make for this reference when I’m around someone who does not watch Malayalam cinema.

You’d think I’d have options other than Malayalam cinema for bonding in this movie-mad nation. My family was addicted to movie-watching in five different languages and thought it perfectly unremarkable. What was a bit unusual was that my paternal grandparents owned a movie theatre in the village for a while. We were packed off, all of us cousins, resident and visiting, to watch whatever raunchy 1980s Malayalam movie was running in the afternoon, to keep us off the streets and out of the pond or the local timber mill where the elephants were diligently working.

For a while, after the afternoon show, I’d race out to the back of the theatre hoping to catch the actors, since I’d somehow imagined that they were just behind the screen. No one worried about what we were watching. Movie-watching was completely respectable in that household. My paternal grandparents even offered to take my mother to the movies to distract her from labour pains when she was about to give birth to me. I suspect if the gimlet eye of her own mother (who was convinced that all in-laws are villains unless proven otherwise) hadn’t been on her, my mother would have gone gamely to the matinée. To see something by Sukumaran, probably, or MG Soman. Soman once turned up in the village to promote his movie and all of us grandchildren were gobsmacked seeing our house surrounded by hundreds and hundreds of fans. We got nowhere near the star, of course. But the stars seemed very close, so close that I’ve a false memory of staring into the sky after being told the breaking news that the action star Jayan had fallen off a helicopter during a stunt and died. An utterly false memory, because when Jayan with the Errol Flynn moustache died, I was just a year old.

After my parents left Kerala, first for Nigeria and then to Oman, their movie addiction continued. They watched British and American cinema (though I don’t think they discovered Nigeria’s own.) There is also some family legend that when we were robbed to the last spoon in Nigeria, my parents were left only with a trunk full of movies which they sold to finance my father’s visa to Oman.

Later, through their decades in Oman, my parents were always members of the local video library in whatever tiny town on the Batinah coast they were stuck in, and watched three or four movies every week. They watched Malayalam, Tamizh, Hindi, Telugu movies and of course, Hollywood. In the summers when my brother and I visited them from India, my mother stocked up the fridge with treats and piled up the videos that she had enjoyed all year.

I was more than happy to plunge into the crazy comedies that she usually picked, particularly because in Bangalore, where I went to school, my movie viewing was rather virtuous. The Kannada movie every Saturday evening (Rajkumar as Krishna, Rajkumar as James Bond) and something horribly cheerful in Hindi on Sunday evenings. The only Malayalam movies I caught on television were worthy national award winners like Adoor Gopalakrishnan and G. Aravindan works which, to my pre-teen self, were parodies of long silences and bewildering ambiguities.

Superficially, I went through the same rites of passage as everyone else of my generation in Indian cities, graduating from Amitabh Bachchan to Shah Rukh Khan, or from Kamal Hasan to Madhavan. But I had no clue what my friend Vinaya was talking about when she says she first understood sexual desire after seeing Amitabh Bachchan in Deewar, or my friend Paro, to whom Shah Rukh means pure love. I found romance in the crevices of Malayalam cinema.

Hollywood was where people tongue-kissed, the same fictional universe as Mills & Boons, where people had no parents and could do anything. Hindi movies had even more baffling people: those who knotted jaunty handkerchiefs around their necks and played pianos. Telugu movies had people doing aerobic routines en masse on shiny disco floors under shiny disco balls. Malayalam movies had Malayalis, who, like me, couldn’t dance, were uncool but snippy. At best, they could look over mountain vistas while clad in knotted sweaters. Mostly, they couldn’t do that either without making fun of themselves.

The climax of one of my favourite movies Mithunam (plot: Sethumadhavan wants to start a biscuit factory but everyone wants a bribe) works around a disastrous romantic getaway to the hills and the hero’s tirade against his long-term girlfriend’s cinematic expectations of love. I don’t know why Sethumadhavan bothered. The entire movie was puncturing romance in cinema. Here is Sethumadhavan and buddy outside his girlfriend’s house planning the quick elopement. Buddy peeps over the bushes and spies a teenaged girl sweeping the courtyard. Buddy: Is this thirteen-year-old the one you said you have been in love with for the last sixteen years? Later, as they are carrying away the girlfriend rolled up in a mat, Sethumadhavan spots his girlfriend’s older brother. Sethu: Oh my god, it’s her brother! Buddy: Is that the elder brother of the burden we are currently bearing?

Why would something so fundamentally anti-romance fizz in my veins?

I don’t want you to think these movies were charmless or nihilistic. They did have the lover who quotes a passage from the Song of Songs (“let us go out early to the vineyards and see whether the vines have budded, whether the grape blossoms have opened and the pomegranates are in bloom. There I will give you my love.”); the woman who scams her neighbour and convinces him that her ‘foreign’ dark glasses give her x-ray vision to see through his clothes; the woman who goes from Bangalore to the funeral of her mercurial lover and finds the identical twin he’d kept in Kerala as a prank; the young wife of the old brahmin who is smeared with the face-paint of her Kathakali dancer lover.

It wasn’t that Malayalam cinema was staid either. I didn’t need to see Silk Smitha to be shocked. Why bother when there was Mammooty in an eye-poppingly tight swimsuit, or heroines in gratuitous towel-wearing-and-playfully-fighting-in-bed scenes? Why bother with item numbers when the worldliness of the script could titillate so much more? Take this scene: aunt of heroine tells her that she’d better marry suitable boy aunt has picked out or else. Heroine refuses. The very next scene: post-coital aunt in bed with suitable boy telling him to not to worry, the heroine will come around or she will be made to.

Or take the mildly arty film I caught one afternoon in which the orphan from the city who is trying hard not to scandalise the village inadvertently (when she is sitting at the stoop of the house she remembers to keep her legs covered entirely under long skirts) and is instead surprised by her first kiss – in broad daylight with a casualness and lack of soothing soundtrack.

It took me years to understand that the romance Malayalam movies offered me lay elsewhere. Somehow it had leaked out of everything from the Keystone Kop comedy of Nadodikkattu to Mithunam, to the political satire of Sandhesam into the real world. Romance lay in the particular comic timing of Malayalis: the deadpan delivery, the unexpected terms of reference, the particular rhythms of speech. Though I speak, read and write Malayalam, I’ve lived very little in Kerala and have no formal understanding of its literature. I don’t know enough to decide whether the Malayali men of my generation speak like the movies or the movies speak like them.

All I know is that a certain rhythm of speech will get me every time because it reminds me of a long history of movies: one collapsing on another with a clang and a crash like the school cycle stand when my friend Nishad came downhill and lost control of his new Hero Ranger. No, to be accurate they fall like the one pot that broke in the beginning of the 1994 movie Thenmavin Kombath (elderly lady to Manikyan: Are you saying the police came because you broke one pot at the market? Manikyan: Well, no, that was probably because the pot I broke had a few hundred pots above it.)

Sometimes it’s a just a silly memory. In my family, we just need to hold up a chilli with a solemn face to crack each other up. It evokes the matriarch of Melaparambil Aanveedu handing her three unmarried sons and her unmarried brother-in-law chillies like swords to take into battle, because gruel and chillies were the only items on the menu henceforth, because she had no plans to cook ever again.

Mostly, though, it’s not just deplorable nostalgia. My favourite exchanges were always the ones that went from grouchy to absurd in three sentences, usually written by the diamond-sharp (writer, actor, director) Sreenivasan. Observe my most beloved sequence ever in Sandhesam, a movie about two brothers who are lowly but rabid members of rival political parties. It’s lunchtime and each brother tries to turn their newly retired father (freshly arrived in Kerala from a lifetime posting in Tamil Nadu and hence, the movie implies, an innocent abroad) towards their side. Impassioned one-upmanship careens from the IMF to the gold standard to the devaluation of the rupee to the puppet government in Nicaragua, the collapse of Hungary, and ends with the Communist brother (Sreenivasan) sternly warning the Congress brother: “Polandine patti oraksharam nee parayaruthu (Don’t you dare say a word about Poland).”

I have my share of affection for Dharmendra and Amitabh Bachchan in Chupke Chupke and I smile politely at people who rave about Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron. So polite that I don’t even think to myself: brother, what would you do if you watched Narendran Makan Jayakanthan Vaka, a surreal, serene comedy that spans the 24 hours of a man (non-resident Malayali freshly arrived in Kerala from Tamil Nadu and hence again, the movie implies, an innocent abroad) trying to get compensation for the property that his father lost to the Kannur Airport? What would happen is that your brains would leak out of your ears.

But I don’t say that. My pleasures remain private.

When I was 24, I was stuck on a project for weeks at a stretch with a pothead designer. He had nothing to recommend him except his general sweetness and the facsimile of Malayalam movie comic timing that I now realise I’m fatally attracted to. The rest of the package – the distrust of emotion, the moping, the languor – I could do without. I did do without.

Years later we bumped into each other on the street. I was hanging out with N, a Malayali friend who speaks less Malayalam than I do and for whom, therefore, Malayalam humor is only accessible as a bittersweet groupie. Obviously, in his presence I like to perform quick acts of Malayaliness. Like teasing a true-blue Malayali in Malayalam. Acquired as my register is from movies which give female characters next to nothing to do or say, my ‘material’ (as the stand-ups say) is necessarily laddish. I’m inclined to say shavam for effect. (What? It means corpse and don’t ask me why it’s a swearword). I’m inclined to say shavam, kundam, myru (corpse, spear, pubic hair) not ‘sheeee’ or ‘cheee’ as ladies ought to.

So there I was doing my number and my lost-lost crush put up with it for a while. He was silent as the tomb as he had always been. When I teased him about something obscure he waited two beats and then said, “oho.” Then another beat. N and I stared. “Vitt-uh.” he completed deadpan. I was slain. Living across the border from Kerala, N and I have to wait for years before there is any context for anyone unleashing that familiar, contemptuous Malayalization of the English word ‘wit’. For N and me, it was better than sex.

* * *

The Malayalam folk rock band Avial has made some inroads into the world of my Malayali and non-Malayali friends in the last few years. Though I like some of their tracks I have an irrational suspicion, a Scrooge-ish resistance to their trendiness among some people I knew.

As Malayalam cinema becomes more globalised, has more globalised faces, bodies and features, embarrassments such as whirling dervishes on Kozhikode beach (oh Ustad Hotel, how I loved you for the first twenty minutes with your screen-full of cute hijabi girls before you pulled your faux-Sufi nonsense on me) I’m rendered more and more cranky.

I saw Neelakasham Pachakadal Chuvanna Bhoomi and pulled my hair out in clumps. The cute-boy protagonists are riding through the country on fancy motorcycles, okay. They are being serenaded through said south Indian countryside by piggybacking rollerskaters, er…okay. But the voice-over in half-Malayalam and half-English made me cry: “They say the road has answers for everything. Enalum enyike chothiyangal ilayaranu. I was confused on (sic) identity, politics, happiness, freedom. The only thing I was always sure about ente vidhi ente thirumanangalanu and I chose to be with her.” This movie may well be somebody’s Dil Chahta Hai but boy, does it look like one giant Delhiyile art journal.

It isn’t nostalgia that makes me resistant to the smart, new movies of Malayalam cinema. It is the knowledge that I may have to wait a long cinematic lifetime before smart patter comes back, absurdity comes back, uncool comes back. For a brief while, my neurotic, shifty sense of humor and desire for self-deprecating romance was in sync with what was on screen. For a brief while, I possessed cinema aglow with men who were not dudes, who were utter failures at being dudes, who broke your heart permanently with their undude-ishness. Their toes were almost always making circles in the sand while the heroines stared bemused at them. When the scripts required them to be jet-setters they looked giggly.

The beginning of the end came with a swathe of macho movies with two-word English titles: The King, The Commissioner (and to our recent horror, a sequel called The King & The Commissioner). The soft, dysfunctional heroes I loved were suddenly bursting out of tight uniforms or uniform-like office gear. Their mouths were filled with tooth-cracking, breathless rants about the evils of the nation and the worse evils of forward women in trousers who have careers.

For a long while I stopped watching Malayalam movies. I switched to Tamizh where luckily the age of the sexy, dysfunctional hero was just around the corner.

My baby cousin Prem (well fine, he is a giant six-foot person now) is my current source for the best things from Kerala. I trust, for instance, that he will not peddle two random boys on bikes surrounded by roller-skaters with a portentous voice-over to me. After all, when I started researching Malayali nurses he blew my mind by making me watch 22 Female Kottayam, the adventures of the bobbitising nurse Teresa Abraham. So when he sends me a link saying watch this, I watch it. Even if it is a video of Avial’s song from the soundtrack of the Malayalam movie Salt N’ Pepper. I’d mildly enjoyed the movie for its slightly stoned and runaway plot about two not-so-young people finding love through cooking.

Revisiting the music video didn’t seem like too much fun. Here were the dudes jumping around doing their dude thing singing in a flood-lit set (with motorcycles and extraneous sofas) about Ayyapan the elephant thief, Ayyapan the yam thief. Why should I care, I thought in my familiar Scrooge-ish way.

And then I saw it. On the dudes’ t-shirts was the almost-impossible-to-read line: “Polandinepattioraksharam nee parayaruthu.”

I won’t say a word about Poland if you won’t.

Nisha Susan is an editor for Yahoo! Originals and the women’s zine The Ladies Finger. Her fiction has been published by n+1 magazine, Caravan, Out of Print, Pratilipi, Penguin and Zubaan, and she is currently working on her first book.

The Temple Connolly Review of Ko Antey Koti.

Ko Antey Koti

Filed under: Tollywood by Temple Connolly — Leave a comment

December 3, 2013

The vintage heist genre has been reinvigorated by the likes of Steven Soderbergh, Guy Ritchie, Choi Dong-Hoon, Abhinay Dey and Akshat Verma. Anish Kuruvilla adds his own stamp with Ko Antey Koti.

The rules of heist films require that the target must be audacious and the very elaborate plan must rely on split second timing and specialist skills. There will be loads of characters with unique talents and many of them are disposable. There must be at least one despicable villain who must have a grievance with the hero. Subplots abound, as do betrayals. Add family or romantic tensions, a heap of flashbacks, and you’ve got the basics.

Sharwanand is one of my least favourite Telugu actors but I will grudgingly admit he is improving a bit. He was terrible in the tedious Gamyam (I refuse to let Heather give me my DVD back), he had moments of adequacy in Prasthanam, and he manages to be convincing as Vamsi most of the time. Vamsi seems to be a criminal through lack of motivation to do anything else rather than any commitment to being an outlaw. Sharwanand is perfectly fine in conversational or romantic scenes. When he has to convey powerful emotions he seems to pause for an instant before deciding what expression to use, and so he seems stilted. Having said that, he has good rapport with Priya Anand and their scenes flow very nicely. He generally plays Vamsi as grumpy and whiny, so his lighter moments with Sathya and the troupe or with Chitti and PC are quite endearing.

There are few Indian cinema leading ladies that look as though they really could travel by public transport or know their way around a kitchen. Go on. Picture Katrina Kaif catching the 86 tram. Priya Anand has a freshness and natural vivacity that plays to great effect in this role. Sathya is a slightly unusual heroine by Telugu film standards as she has a brain and uses it. She is voluble and a bit too inclined to Do Good through street theatre, but her chatter is often a tactic to bulldoze over any objections.

People find themselves doing as she asks even though they had no intention of agreeing. I’m not convinced that her dance students would learn much, but the kids seemed to enjoy leaping about with her. Sathya’s determination to lead a socially responsible life makes sense when more of her family story emerges. Her relationship with Vamsi is complicated by a shared connection neither knows of. The past is hard to escape, even when it isn’t your own.

The late Srihari is the criminal mastermind, Maya. Maya is crude and has no love for anything except money. He uses people to get what he wants and has no compunction about terminating an association. Srihari dominates the confrontational scenes with total ease. This works quite well considering Vamsi and the other sidekicks are supposed to be relatively unthreatening. I questioned why he would hire so many idiots but all became clear. Srihari gives Maya a plausible charm, as long as you don’t look too closely at the calculating eyes. And you forgive the dodgy wig. It’s another in a long line of bellowing patriarchal figures for Srihari but he brings it and Maya is a despicable man.

The romance between Sathya and Vamsi is developed in ways that are credible yet still entertaining. One of the things I liked most about Kuruvilla’s Avakai Biryani was the way relationships grew and were strengthened through shared small moments, and he is similarly detailed in this story. Even the romantic sideplot with Chitti and a prostitute was funny and a little touching. Sathya helps Vamsi because he needs help, not because she is smitten with insta-love for The Hero. She chooses to be a happy and good-natured girl, and her open heart allows Vamsi the opportunity to see himself as he could be if he made different choices.

Anish Kuruvilla added some fun flourishes. Sparks literally fly when the couple kiss and no filmi cliché is overlooked as they prance through a gloriously pretty montage. Vamsi acts the part of an actor and proposes on stage, being more honest in his pretence than as himself.

Sex is treated in a non-scurrilous manner. Sathya was actually wearing more fabric when swaddled in her bedsheets than in any of her sarees. I cheer for a heroine who doesn’t have to die immediately after she sleeps with her boyfriend, and it is refreshing to see consensual and mutual attraction between the lead characters. I also liked that Vamsi acknowledged Sathya’s right to have some input into a critical decision. It wasn’t a grand speech, but a moment that showed their pragmatism and trust in each other.

Cinematographers Erukulla Rakesh and Naveen Yadav captured the different worlds the characters inhabit. The light is harsher and the shadows deeper in Maya’s criminal milieu, places full of twists and turns, the suggestion of hidden watchers. Vamsi and Sathya fall in love in a much more colourful and soft setting, a rural paradise and open skies that give space for dreams. The final scenes are in an arid landscape as everything is laid bare and no secrets remain. I really liked the styling of the seedy nightclubs, the squalid apartments, the activity humming through the street scenes. There is a strong sense of place and a modern feel to the sharp edits and angles.

The abundance of incidental characters can mean that characterisations are sketchy. Gluttonous PC (Nishal) and scrawny, one-eyed Chitti (Lakshman) play it as broad as can be. There is no subtlety. Perhaps because of my allergy to Indian film comedy, I was not even slightly sad to see some sidekicks bite the dust early on. If someone minor has a tragic backstory or is the butt of all jokes, do not bet on that character making it to intermission. Corrupt policeman Ranjit Kumar (Vinay Verma) is on the trail of the stolen goods and has his own grudge against Vamsi and Maya. He is a type rather than a realistic or subtle interpretation, but that wasn’t a drawback. The fun of this genre is the guessing and double-guessing rather than delving into a layered psyche.

The songs are used very well and to an extent they amplify characters’ inner lives. I was not overly impressed by the picturesque wandering and montages – I like a big dance number or two. Shakti Kanth has chosen to use different styles of music that match with the action and help build the atmosphere.

It’s refreshing to see a boys own adventure have interesting female characters. There is a little more realism to some of the relationships and there are some gorgeous visuals. The comedy sidekicks are neither funny nor interesting so I tuned out while they were doing their thing. I’m still not convinced by Sharwanand but Priya Anand and Srihari are great. Kuruvilla juggles the elaborate setup and flashbacks in a structured way that feels dynamic but is still logical so I never felt I lost the internal timeline. He’s a realist, especially about traffic and human nature. Well worth a look, especially if you like a more urban gritty thriller. 3 ½ stars!

http://cinemachaat.com/2013/12/03/ko-antey-koti/

EXPERIMENTS WITH LIGHT

via Facebook https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10152116279424343&set=a.224945474342.165714.678474342&type=1

Tuesday, December 03, 2013

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Tuesday, November 05, 2013

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

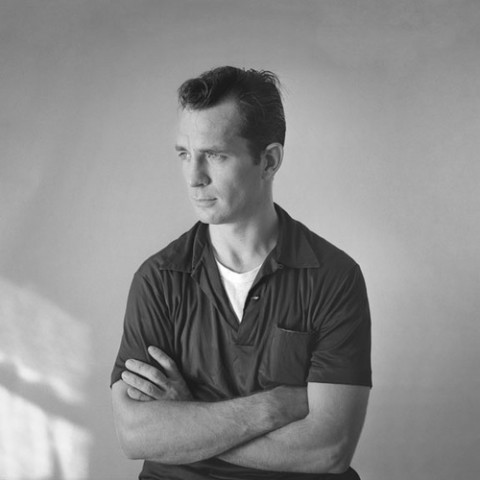

Jack Kerouac Lists 9 Essentials for Writing Spontaneous Prose

Jack Kerouac wants you to turn writing into “free deviation (association) of mind into limitless blow-on-subject seas of thought, swimming in sea of English with no discipline, other than rhythms of rhetorical exhalation and expostulated statement….” Think you can do that? Find out by following Kerouac’s “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose.” He published this document in Black Mountain Review in 1957 and wrote it in response to a request from Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs that he explain his method for writing The Subterraneans in three days time.

And for a theory of Kerouac’s not quite theory, visit the site of Marissa M. Juarez, professor of Rhetoric, Composition, and the Teaching of English at the University of Arizona. Juarez raises some salient points about why Kerouac’s “Essentials” bemuse the English teacher: His method “discourages revision… chastises grammatical correctness, and encourages writerly flexibility.” Read Kerouac’s full “Essentials of Spontaneous Prose” here or below. [Note: If you see what looks like typos, they are not errors. They are part of Kerouac's original, spontaneous text.]

SET-UP: The object is set before the mind, either in reality. as in sketching (before a landscape or teacup or old face) or is set in the memory wherein it becomes the sketching from memory of a definite image-object.

PROCEDURE: Time being of the essence in the purity of speech, sketching language is undisturbed flow from the mind of personal secret idea-words, blowing (as per jazz musician) on subject of image.

METHOD: No periods separating sentence-structures already arbitrarily riddled by false colons and timid usually needless commas-but the vigorous space dash separating rhetorical breathing (as jazz musician drawing breath between outblown phrases)– “measured pauses which are the essentials of

our speech”– “divisions of the sounds we hear”- “time and how to note it down.” (William Carlos Williams)

SCOPING: Not “selectivity” of expression but following free deviation (association) of mind into limitless blow-on-subject seas of thought,

swimming in sea of English with no discipline other than rhythms of rhetorical exhalation and expostulated statement, like a fist coming down on a table with each complete utterance, bang! (the space dash)- Blow as deep as you want-write as deeply, fish as far down as you want, satisfy yourself first, then reader cannot fail to receive telepathic shock and meaning-excitement by same laws operating in his own human mind.

LAG IN PROCEDURE: No pause to think of proper word but the infantile pileup of scatological buildup words till satisfaction is gained, which will turn out to be a great appending rhythm to a thought and be in accordance with Great Law of timing.

TIMING: Nothing is muddy that runs in time and to laws of time-Shakespearian stress of dramatic need to speak now in own unalterable way or forever hold tongue-no revisions (except obvious rational mistakes, such as names or calculated insertions in act of not writing but inserting).

CENTER OF INTEREST: Begin not from preconceived idea of what to say about image but from jewel center of interest in subject of image at moment of writing, and write outwards swimming in sea of language to peripheral release and exhaustion-Do not afterthink except for poetic or P. S. reasons. Never afterthink to “improve” or defray impressions, as, the best writing is always the most painful personal wrung-out tossed from cradle warm protective mind-tap from yourself the song of yourself, blow!-now!-your way is your only way- “good”-or “bad”-always honest (“ludi- crous”), spontaneous, “confessionals’ interesting, because not “crafted.” Craft is craft.

STRUCTURE OF WORK: Modern bizarre structures (science fiction, etc.) arise from language being dead, “different” themes give illusion of “new” life. Follow roughly outlines in outfanning movement over subject, as river rock, so mindflow over jewel-center need (run your mind over it, once) arriving at pivot, where what was dim-formed “beginning” becomes sharp-necessitating “ending” and language shortens in race to wire of time-race of work, following laws of Deep Form, to conclusion, last words, last trickle-Night is The End.

MENTAL STATE: If possible write “without consciousness” in semi-trance (as Yeats’ later “trance writing”) allowing subconscious to admit in own uninhibited interesting necessary and so “modern” language what conscious art would censor, and write excitedly, swiftly, with writing-or-typingcramps, in accordance (as from center to periphery) with laws of orgasm, Reich’s “beclouding of consciousness.” Come from within, out-to relaxed and said.

Oh, and for authenticity’s sake, you should try Kerouac’s “Essentials” on a typewriter. It’s all he had when he wrote The Subterraneans. No grammar robots to distract him.

............................

Wednesday, October 09, 2013

Sunday, October 06, 2013

The Hyderabad Situation by Mohan Guruswamy

The

ongoing battle between Andhra and Telangana politicians of all hues and

colors is for control of Hyderabad. It is the milch cow that hads been

milked dry by these corrupt politicians. The city has not had a

democratically elected local government for decades and is run by a

junior IAS officer, who is at the beck and call of the CM's and the

Municipalities minister's. All zoning rules have been abandoned and all

building regulations have been given the go by to enable the real estate

lobby and aligned politicians to make good. The people of the twin

cities have been the real victims for the last six decades.

Hyderabad and Secunderabad were beautiful and well laid out cities till

the district politicians got hold of it in 1956. Since then it has been

turned into a giant slum. Every major leader who is now fighting on

either side of the Andhra-Telangana divide has got huge real estate and

commercial interests in the twin cities. You name him and he is on the

list. Chandrababu Naidu, Jaganmohan Reddy, KS Rao, Lagdapati Rajagopal, G

Venkatswamy and now KCR. I can run off a comprehensive list of big and

even lesser netas like Devender Goud. But that list will need more than

this page.

The twin cities are still largely cosmopolitan in

character with people from all parts of the country as its residents and

that character needs to be protected. They are neither Andhra or

Telangana cities. They have given India singers like Pandit Jasraj,

poets like Maqdoom Mohiuddin, film directors like Shyam Benegal, actors

like Suresh Oberoi, Army, Airforce and Navy chiefs like Gen. Srinagesh,

ACM Idris Latif and Admiral Ramdas Katari. And groomed leaders like PV

Narasimha Rao, Veerendra Patil and Shankar Rao Chavan. Even now the

majority of its residents are Hyderabad and Secunderabad born. All of us

locals have a pretty good idea who we are, But it is these

johnny-come-lately's who are giving the twin its cities extravagant

geneologies, such as a 2000 year old history and thus laying claim to it

The facts are otherwise.

Hyderabad was established in 1591 by

Quli Qutab Shah of Golconda, and was first named Bhagyanagar after his

beloved and paramour, the courtesan Bhagmati. He penned the immortal

verse expressing his love for her : "piya bin piyaa jaaye na, piya bin

jiyaa jaye na!".

Secunderabad was established in 1806 and was

named after Sikandar Jah, the third Nizam. It housed the British

garrison and was British controlled town till 1948. The 19 Hyderabad

Regiment became the main element of the Kumaon Rifles, and the 13 Kumaon

battalion that won immortality in Rezang la in 1962 was originally the

Ahir composed 13 Hyderabad battalion.

The Twin Cities are

centrally situated and have a generally salubrious climate. They have a

distinct culture that is well known all over the country and even world.

Jawaharlal Nehru often thought of it as a second capital of India. He

wanted at least session of Parliament to be held here each year. Thats

why the Presidents of India retire to Bolarum for a few weeks every

year. It could have been a great city, but these wretched politicians

have turned it into a giant milch cow tethered to one idea and made to

wallow in its own squalor.

Friday, October 04, 2013

The Anand Gandhi Interview

The Anand Gandhi Interview

Runcil Rebello (RR): Tell me something about Anand Gandhi as a child. What did he read, what films did he watch?

Anand Gandhi (AG): I’ve been exposed to a barrage of images and ideas and thoughts as a child. My grandmom was a spiritual shopper… is a spiritual shopper. She would spend a lot of her days going to satsangs and meeting gurus of all kinds and totally into that. She would say I’m not into religion, I’m into these guys. I’m into sant log. I used to go around with her. My mum was a Bollywood fanatic. She’s a romantic. She loves romantic, sentimental poetry. She used to read Barkat Virani – this very romantic, sentimental poet. Equivalent of Ghalib in Gujarati. And she used to read him as a teenager and think that she would grow up to marry him someday. And I’ll cure him of all his pain and all his hurt. She was like that. She used to expose me to poetry, to cinema, to lots of theater, she used to take me to all these plays, and I would come out of them and say “this is an amazing experience”. I was 5-6 years old and I would be “I can do this, right?” and she would be like “Of course, you can. Why don’t you do it? Why don’t you write a play?” I was six years old when I wrote my first play, and my mom looked at it, and said, “This is genius.” It was highly encouraged. There was always a sense of the tiniest things that I was doing – there was a constant resonance, a constant reflection which was incredibly encouraging and very helpful.

So I saw a lot of cinema, lot of pop cinema, largely Bollywood. Hollywood for us at that time – I’m a child of the eighties – meant Jackie Chan, dubbed Jackie Chan, actually, and Honey, I Shrunk The Kids – like that. So that was the only exposure I had, but the consumption was very high. Also, the fascination ran very deep in everything, and I was encouraged to go all the way. So I wanted to pursue magic very seriously. My mom contacted a magician and asked him to come train me at home and he would train me in small card tricks, and table-top tricks. I spent a lot of time reading magic books and creating my own devices. This was when I was 7-8 years old. I really wanted to grow up to be a scientist. I always imagined that I will become a theoretical physicist someday. At that time, it was a scientist of course, I didn’t know what a physicist meant. Oh wow, Newton and Galileo, they were just like me when they were children. So I used to be fascinated by these ideas, and I was always encouraged.

I think there were a lot of disadvantages that became advantages at some point in time. For instance, a complete disinterest and a lack of aptitude in sport. Lack of a muscular body, I was really fat, absolutely no enthusiasm allowed me to do a lot of things that was entirely exciting and fascinating and on the other hand was compensatory. Compensating for the inability to be able to relate to children in the chawl I was growing up in. That was what childhood was like. Resources was limited, lived in a single room made of crude sheets of tins, brick walls, no tiling. That was natural, a way of life. It wasn’t perceived or communicated as an absence of resources. Everything that had to do with intellectual pursuit was highly encouraged. Science was encouraged, magic was encouraged, writing was encouraged, painting was encouraged – all sorts of intellectual pursuits were highly encouraged. Sacrifices were made by my mum and grandmum so I could pursue my notions of being an inventor – which I thought I was when I was nine years old. They would leave their jobs at hand or take to long-distance tours just to bring me things that I had read on books, material that you just cannot find anywhere. We’re talking of stuff like ‘spring with the caliber of so-and-so’, ‘0.3 mm of so-and-so’. Where the fuck am I going to get something like that? If you want to make a motor or a seismograph, and you try to make them because everything has been replaced by something else, and they would fall apart. But everything was encouraged. Choices were encouraged. Like when I was 8 or 9, I just told my mother that it doesn’t make sense that people burst firecrackers during Diwali. It’s not attractive, it’s incredibly irritating, it produces this noise – I was damn irritated by it as a child. I could not see how anyone was attracted to lighting a sutli bomb. I was like it produces a huge band, so what? It didn’t make any sense to me. So when I was 9 years old I went to my mom and told her this Diwali onwards I’m not going to burn any crackers. So do you you have a budget kept aside for anything like that? So she was like yea, I have forty bucks. So I was like Children’s Knowledge Bank Part 3 costs 18 rupees, so maybe I can buy both part 2 and part 3, which were the books I’d read for my Homi Bhabha Science competition which happens in classrooms.

RR: Your parents must have been very happy with you.

AG: I was very academically inclined, I was very attracted to knowledge. Deeply attracted to knowing and finding, I was extremely curious. And that was encouraged.

RR: So you’ve always had this ‘explorer’ streak within you. When did storytelling enter the scene?

AG: It was a part of it. Only later in life was I able to see the continuum between all of them. Because especially when you’re growing up in India, you are always told “you can only do this.” The rest all is hobby. When you’re raised in that kind of an environment, where there is no infrastructure to groom a certain kind of thinking, a certain kind of envisioning, you kind of fall back on what is available. I was attracted to everything at the same time. I could not choose one over the other. I did not see why I had to choose one over the other. And that’s the reason I dropped out of college also. I just couldn’t consign to the idea that you could choose only one; it just did not make any sense to me. I was like, I’m incredibly interested in scientific inquiry, I’m interested in the inferences of physics, of microbiology, and neurosciences. But what do I do with that information if I don’t have the philosophy. If I don’t interpret the information being produced by scientific inquiry, that information is meaningless. What is this God Particle? What is this Higgs Boson? If I’m not able to interpret the information produced by the scientific inquiry, then it’s of no use to me. I need to know how it changes my life, I need to know how to use it to become a better person. How can I use it to make life around me better, more beautiful and engaging? So ‘satyam’ by itself is of no use, ‘shivam’ and ‘sunderam’ is also necessary. I need to use the satyam – the fact – produced by scientific inquiry and juxtapose it with the environment, with myself, with everything around and put a meaningful structure to it. Then I’ll find my role really relevant if I can take that inference, take that assimilation and weave it into narrative metaphor so that it can reach a really wide audience because that’s how inquiry has reached me. I was enlightened by cinema, you know, I was informed by cinema and theater, I came to know of a lot of things in life because of popular cinema and theater. So I thought it’s such a powerful medium and as I grew older I realised it is being utterly under-utilised. It’s a medium that can, while actually engaging you in a story, while engaging you in narrative, while entertaining you, it can/has the potential of actually enlightening you. It has the potential of bringing a rich and profound experience in you, profound epiphanies in you. Also, I became increasingly attracted to playing that role in life – That I can be magician, a scientist, a philosopher, an actor, a writer, – all of that together if I become a filmmaker.

RR: You’ve talked about entertainment and enlightenment. Which films in the recent past have you felt manage to do both?

AG: A lot of film. The Turin Horse was that for me. But it won’t be considered entertaining by a lot of people. For me it was engaging, entertaining and enlightening. Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon was truly engaging and enlightening. Holy Motors was one film – there was a different kind of enlightenment – it opened up areas of examining – triggers – for me. Like how triggers can be triggers for triggers for triggers for experience. The whole sophistication of its simulation system was so high-end, so amazing. That enlightened me while entertaining me recently. And there are lots of other films. One film that was for me hugely entertaining, that was a big boost in my wanting to make films after that was The Matrix. I was 17 years old when I saw the film. I was just blown away by it. All the ideas that I’ve ever thought about, all the ideas that I’ve ever been attracted to, the idea of simulation, the idea of illusion, the idea of examining reality, social constructs, religious constructs, evolution of religion. All these ideas are in there with so much entertainment, so much accessibility. When I was 17, it just meant so much to me that time.

RR: Coming to Ship Of Theseus, why the eyes, the liver and the kidney? Why these three organs, or were there more while scripting?

AG: There were other organs as well. The initial idea was to make a story about 8 people. Then when I wrote the script, I wrote it about four people. There was also a heart. And by the time I started shooting, I started realising “This is going to be a very long film with three stories itself.” The fourth one in there is not going to be a film. It’s going to be a prolonged experience of some kind. It would have been a four hour long film. It would have been an impossibility. It was only due to the limitations of the medium. At the end, you can watch a film at a stretch for two and a half hours max.

RR:

There are people who have watched the film and said “It isn’t complex.”

But there are many others who think the film is complex and some think

it is a talkie. How do you intend to dispel these qualms, or are you

even trying to dispel them?

RR:

There are people who have watched the film and said “It isn’t complex.”

But there are many others who think the film is complex and some think

it is a talkie. How do you intend to dispel these qualms, or are you

even trying to dispel them?

AG: We are all equipped with different kinds of language. We are all equipped with different idioms. And we have all been informed and groomed by a series of experiences and education. Now within that paradigm, each one of us is going to have a certain kind of a _______ (audio unclear) My attempt would be to make the film as vast as possible. There is something in it for everybody. I’m Gujarati. I was raised in a culture where you have the thali. I was raised on popular culture where there is a thali on film also. Hindi popular film is where you have comedy, and dance and tragedy and romance. At an essential level, that is what I’ve done with Ship Of Theseus. It’s a film where you have so many ideas. It also has three filmmaking styles in it. Each story has been made in a different style. The approach has been completely different. So the first film is not that dependent on conversation, the third film is not that dependent on conversation. The second film is driven by the discourse. The first film is driven only by the image. The third film is driven only by the relationships: the interactions and the emotions. So each filmmaking style is different, each cinematographic style is very different. The film is really vast and the attempt is to have the range of experiences that we have had which is usually chaos. Because the magnitude of human experiences is so vast, and to fit it down into a reduced, bumper sticker is incredibly difficult. But that has been the inspiration, to pin it down, to nail down with rigour that it’s meaningful as a whole. And also the aspiration is that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The parts are extremely transparent and visible. If you see the parts unfolding one after the other, you can see the parts, enjoy the parts, and suddenly when it comes to the end, you have an experience where you’re like how did this happen? How did the whole – this experience that I have had is suddenly so much greater than the sum of the parts that I just saw. That is the aspiration, that is the attempt. I feel that some people have felt that way, at least.

RR: How was it after the World Premiere at Toronto where it got unanimous acclaim? What were your expectations, and did you get that?

AG: See the problem with an optimist is that you’re not pleasantly surprised. I’m an optimist. One of my closest friends is a cynic. He’s a pessimist. He says, “Toronto mein itne logon ne bol diya life-changing film hai, usse pav-wada wala thodi tujhko extra chutney dega.” So he’s always happily surprised. I’m never happily surprised because I expect the best and when it happens, I’m like, “alright, it was expected.” What I’d expected at Toronto was that the cinephile community, that the film will give a very deep and profound experience to some people. That I’d expected. What I’d not expected was that it will give a profound experience to everyone. That was unexpected. We were walking the streets of Toronto and people were coming and hugging us, “My life has changed, I’ve never experienced anything like this before.” That was still happily surprising.

RR: What was the situation of the release of the film before Kiran Rao entered the scene?

AG: We hadn’t talked to anyone yet. We were going to talk to some people. We were talking internally about reaching out to some people, but there were no serious talks, no serious engagements with anyone. We were still doing festival rounds. “Baad mein dekha jaayega.” And Sohum Shah is also like a mad visionary. Because he was acting in the film and he believed in the film so much, he’s like “You’re saying that the film is unprecedented. How can you expect anyone to understand something that is unprecedented?” Because I was looking for financing at that time, and he was rehearsing with me everyday. I would go to multiple producers and their reaction would be “This is amazing. Kya script likha hai! Kya kahaani hai! Wow. Par yeh India mein nahi samajh mein aayega logon ko.” The presumptuous arrogance is that ‘Main bahut intelligent hoon, mujhe bahut samajh mein aaya, main keh sakta hoon bahut kamaal hai. But Indian audience nahi samajh paayegi. Indian audience bechaare log hai.” That’s a presumption about 1/5th of human population. So Sohum would tell me, if we know there’s no precedence to anything like this, what reference do we have? He empathised with those people. “They’re businessmen. Unko kya pata hai yeh product ko kaise sell karein. Mujhe pata hai. So we should support it. I’ll put in all my money. Don’t worry about it. Go and make this film.”

He’s a bit of an anarchist, a visionary. Like fuck everything, we’ll do it our way. It’s also because of someone like him, the film could happen.

RR: How do you think Kiran Rao is going to help you get more of an audience?

RR: How do you think Kiran Rao is going to help you get more of an audience?

AG: See, Kiran is an amazing woman. She’s so driven and passionate about the cinema she loves. And it’s been a while since she said that a film has meant so much to her. She loved the film. She said that “I have not had this kind of a cinematic experience in the longest time.” You tell me, what’s next. We started talking about life, universe, cinema. We became really good friends, and in that period I kinda suggested about the possibility of her presenting the film. For the last few years, she has already engaged with a lot of audience. She’s made Dhobi Ghat, she’s produced Peepli [Live]. She knows the infrastructure very well. She knows this particular audience very well, who is a certain audience for this film. She also knows how to use the infrastructure to expand into the audience, who yet don’t know that they want to see this film. I feel there is a huge audience out there who haven’t sampled this kind of cinema and who hence don’t know yet that they want to see this. Once they see it, they would completely get hooked on to it. They would be like, “Oh fuck, yeh kyun koi nahi banata?” You look at youtube, twitter reactions, and people are saying life-changing experience, etc., there is also an audience how is saying “humne aisa kuch dekha hi nahi hai. Why don’t people make this in Bollywood?” So there is an audience that has not yet had a privilege that I had when I was 17 years old, who will come to this film and say this is the kind of cinema we want to see. And Kiran becomes a great medium for that kind of a communication. She’s already established an infrastructure, she already has access to a huge audience with whom she has been engaging with. She has also gained a huge amount of trust with distributors and exhibitors. She has brought in a huge amount of force that is becoming the vehicle of the film.

RR: Since you are now familiar with them, if you have a script for Aamir Khan, would you approach him?

AG: Yes. In fact, Aamir has shown a lot of enthusiasm, he loved Ship Of Theseus, he said that if you have anything that I could do, he would love to do it. He said whatever you are writing next, he would love to look at it, love to read it and see if that excites me. I wouldn’t mind that either. But the thing is, I can imagine Aamir giving that type of a commitment. You have seen the actors that are committed to the films I have made so far. The commitment is of a very severe level. The opportunity, costs become greater. Sohum Shah just spends an entire year doing that film. He eats, breathes, lives that film. When he was doing Ship Of Theseus, he put on weight, he became paunchy, he looks very different. He transformed, he changed his body language. He added small things. Neeraj Kabi, he lost 17 kgs. The commitment was 4 months before the shoot, he started getting rigourously involved with the philosophy of the film. So he became the philosopher he’s supposed to play first so that when he says those lines, it comes out with a sense of commitment. He went from being a non-vegetarian to a vegetarian. He committed to the rigourous diet that the film required him to go through. So the films that I’m making require a huge amount of commitment. I’m certain that if Aamir is convinced about the film, he would be willing to give in to that kind of a rigour. So that’s a relationship I’m completely open to.

RR: You’re pretty lucky getting a release on such a huge scale. How would you feel if you were in the place of an indie filmmaker who has made a good film which is not getting an opportunity for a release? Would you be jealous of yourself?

AG: My peers have been very kind to not be jealous or communicate any jealousy to me. They’ve all been very excited about the release. I understand your question. I’ve been fortunate to have found the crew, actors, producer I found. Found Kiran eventually. Just been a series of good fortune for me. For somebody who has not had that, for somebody who has made a film that is good, that is not necessarily pathbreaking, because you can’t always expect cinema of that kind. A film that is good, that can mean something to some people, that can have resonance and still not finding release – it’s a really bad situation then. It’s a situation that needs amendment, it’s a situation that needs very active audience participation. For instance, if there’s corruption, they need to come on the street and fight corruption. If we are not getting our basic amenities, we need to come on the streets and fight for it. Similarly, when out culture is so impoverished, is so poor and so low-brow, we definitely need to come to the streets and fight for a better culture, better ideas, because our life depends on culture. Our collective well-being, our social well-being, our economy depends on our intellect as a people. And films are the biggest medium for that kind of enlightenment. So I think people should participate in it very actively. The state should take a very active responsibility. It’s annoying that the state is not considering cinema as an important cultural vehicle for bringing about a social change, an intellectual evolution, a collective dialogue and introspection among people. Cinema around the world is such a powerful medium for that kind of an engagement. It is really a shame that the state is not looking at it that way. A certain kind of cinema should be tax-free. Tax should be totally lifted from cinema as a product of culture because it is something that will enrich us as a society.

RR: How has the entire experience of making the film and releasing it now changed you as a person?

AG: It’s very transformative. Growing up, you read about Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak and from other filmmakers from around the world like Ingmar Bergman, how one film completely transforms you as a person. And you think it’s a romantic expression, you know. It’s only after you have gone through this process, I have realised how physical it is, how real it is. It’s incredibly real – the transformative experience. I’ve gone through an exponential change I’ve become much larger than what I started out as. And I feel more calm, more secure. I feel more enlightened. I feel better about myself as a person. I feel I’m more equipped to do things. I also have grey hair. I only had black hair when I started out. One film made my hair go grey.

RR: If you had to discuss your script with your peers, who would you go to?

RR: If you had to discuss your script with your peers, who would you go to?

AG: Khushboo Ranka, who worked on the story of Ship Of Theseus, she’s just one powerhouse of talent, and her vision and her talent is incomparable. She is right now in Delhi directing a documentary that I’m producing. Kiran is someone I’ve begun to trust, begun to rely on, begun to love talking to. The reflections she comes up with, the nuances she comes up with… she’s so compassionate, she’s so effervescent, and enthused, loving and generous. And she always brings in perspectives that are extremely human and empathetic to every idea I discuss with her. Megha Ramaswamy – she’s one of the brightest minds we have right now. She’s just extremely deep in her understanding of beauty and aesthetics, in her vision as a filmmaker and a writer. Chaitanya Tamhane is making his new film, Court, which is currently in post-production. Pankaj Kumar, my DoP, as far as I am concerned, I can say this, he is really the greatest artist working in India right now. He shot Ship Of Theseus, he shot Thumbad, he’s already been awarded four international awards. Everywhere in the world, they are saying this cinematographer, his vision is the newest vision. Transylvania people were ballistic “What the fuck was that?” “How can one see something like that?” I go to him right when I have an idea.

RR: What are your forthcoming ventures?

AG: Thumbad is in post-production. I have produced it, Sohum Shah has acted in it. Rahi Barve directed it. Rahi had shot his short film called Manja, that was really celebrated, everyone had loved it. It did rounds of festivals, won awards. Danny Boyle called it one of the most important films to come out of India. He distributed it on the Slumdog Millionaire blu-ray. This was also shot by Pankaj Kumar. Lot of people around Boyle at that time said that it’s better shot than Slumdog. And it is. Anthony Dod Mantle is a great cinematographer. But Pankaj Kumar is Pankaj Kumar. He’s a genius.

RR: Anything that you are writing for yourself to direct?

RR: Anything that you are writing for yourself to direct?

AG: I’m writing a lot of things. There’s one film from that that we’re doing very soon. Again, with Sohum in it. But I’ll have to work more on it to make it presentable.

RR: Is there any genre that you as a director wouldn’t tackle?

AG: I’m not really attracted to gangster films. I just don’t get it. What’s so exciting about people killing each other? Like really stupid, frivolous people killing each other. I just don’t get it.

RR: So you didn’t like Gangs Of Wasseypur?

AG: I don’t get it. Like karne mein kya hai, I can even like jokes cracked by my friends. I don’t understand what’s so cool about making a film about gangsters. Unless there is an inquiry into it. Unless you’re informing me about the nature of revenge, the primitive need to avenge another, the social need for such a thing to occur and sustain. If you’re informing me in a very intellectual manner and a true discourse. If you’re showing me what’s happening, also show me why it’s happening, and not superficial reasons – not “politics make gangsters”. You know, like, deeply profound reasons of why something like that exists in the first place, which engages in at rue discourse, which enlightens me about – oh, this is the nature of violence, this is the nature of revenge, this is the nature of trying to capture resources through violence. If it’s informing me in a very deep way about something, then yes. But I don’t know anything like that.

RR: What kind of a director are you? Do you tell your actors I want stuff like this and this, or do you give them the script and let them do what they want?

AG: It’s actually both. See, before and after reading the script, they spend a long period of time with me. So I need to have a deep and personal connection with each and every actor I’m working with, so that I can communicate with them. The communication channel in my case becomes so transparent and it’s so strong that my actors and I fully and completely understand each other. Before even handing them the script, I’ve engaged them in a series of debates, a series of questions, a series of experiences that that character would have had. Then I give them the script. So at the script level, they’ve already gone through a long process, and even after that they go through a long process. So it’s a very rigorous and tedious approach.

RR: About your Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi days, did you ever at that time, that you would be stuck here, and no one would ever be able to hear your voice, read your stuff?

AG: I was very young at that time to have any serious insecurity. I had very small insecurities. Will I be able to do things I wanna do? Will I be able to learn, educate, travel? Will I be able to make a film? So while writing Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi and Kahaani Ghar Ghar Ki was a great experience it was actually putting me in a space where I was writing constantly something that was meant for mass consumption, while I was also writing plays that was meant for consumption of a small group of people. So it was a great place to be in to be able to experience both the distinct types.

RR: So you were certain that somewhere down the line, you would be able to get people to listen to you.

AG: I was very certain about it. I don’t know, I feel you need a certain amount of naivety to be so certain. You need to be a little innocent to be so certain. It’s like “arre yaar, apne se nahi hoga toh kisse hoga?” certainty and that’s a good driving force.

Runcil Rebello (RR): Tell me something about Anand Gandhi as a child. What did he read, what films did he watch?

Anand Gandhi (AG): I’ve been exposed to a barrage of images and ideas and thoughts as a child. My grandmom was a spiritual shopper… is a spiritual shopper. She would spend a lot of her days going to satsangs and meeting gurus of all kinds and totally into that. She would say I’m not into religion, I’m into these guys. I’m into sant log. I used to go around with her. My mum was a Bollywood fanatic. She’s a romantic. She loves romantic, sentimental poetry. She used to read Barkat Virani – this very romantic, sentimental poet. Equivalent of Ghalib in Gujarati. And she used to read him as a teenager and think that she would grow up to marry him someday. And I’ll cure him of all his pain and all his hurt. She was like that. She used to expose me to poetry, to cinema, to lots of theater, she used to take me to all these plays, and I would come out of them and say “this is an amazing experience”. I was 5-6 years old and I would be “I can do this, right?” and she would be like “Of course, you can. Why don’t you do it? Why don’t you write a play?” I was six years old when I wrote my first play, and my mom looked at it, and said, “This is genius.” It was highly encouraged. There was always a sense of the tiniest things that I was doing – there was a constant resonance, a constant reflection which was incredibly encouraging and very helpful.

So I saw a lot of cinema, lot of pop cinema, largely Bollywood. Hollywood for us at that time – I’m a child of the eighties – meant Jackie Chan, dubbed Jackie Chan, actually, and Honey, I Shrunk The Kids – like that. So that was the only exposure I had, but the consumption was very high. Also, the fascination ran very deep in everything, and I was encouraged to go all the way. So I wanted to pursue magic very seriously. My mom contacted a magician and asked him to come train me at home and he would train me in small card tricks, and table-top tricks. I spent a lot of time reading magic books and creating my own devices. This was when I was 7-8 years old. I really wanted to grow up to be a scientist. I always imagined that I will become a theoretical physicist someday. At that time, it was a scientist of course, I didn’t know what a physicist meant. Oh wow, Newton and Galileo, they were just like me when they were children. So I used to be fascinated by these ideas, and I was always encouraged.