Saturday, October 15, 2016

Scorsese On Todays Cinema

Monday, December 07, 2015

Music in the silent film era

Music

MUSIC IN SILENT FILM

Film music was largely live in the silent cinema but its practice was specific to the various cultures and nations where it was heard. In the United States phonograph recordings were sometimes used in early film exhibition; in Japan the tradition of live narration extended throughout the silent period. The notion of pairing film and music had a number of antecedents, among them the nineteenth-century stage melodrama. The conventional explanation for the use of music in silent film is functional: music drowned out the noise of the projector as well as talkative audiences. But long after the projector and the audience were quieted, music remained. Music eventually became so indispensable a part of the film experience that not even the advent of mechanically produced sound could silence it (although for a few years it looked as though it might). Film is, after all, a technological process, producing larger-than-life, two-dimensional, largely black and white, and silent images. Accepting them as "real" requires a leap of faith. Music, with its melody, harmony, and instrumental color (not to mention the actual presence of live musicians), fleshes out those images, lending them credibility. Further, music distracts audiences from the unnaturalness of the medium. Adorno and Eisler even posit that film music works as a kind of exorcism, protecting audiences from the "ghostly" effigies confronting them on the screen and helping audiences, unaccustomed to the modernity of such sights, "absorb the shock" ( Composing for the Films , p. 75).

The history of musical accompaniment in the United States has yet to be fully written, but this

Bernard Herrmann scored the shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock'sPsycho (1960) entirely for strings.

important work has begun. Martin Marks, a musicologist and silent film accompanist, finds that original scores existed as early as the 1890s. The scholar Rick Altman shows that in the crucial early periods of silent film exhibition, continuous musical accompaniment was not the normative practice, and he provides compelling evidence that accompaniment was often intermittent and sometimes nonexistent. The US film industry began to standardize musical accompaniment around between 1908 and 1912, the same period that saw film's solidification as a narrative form and the conversion of viewing spaces from small, cramped nickelodeons to theatrical auditoriums. Upgrading musical accompaniment was an important part of this transformation; attempts to encourage the use of film music and monitor its quality can be traced to this era. Trade publications began to include music columns that often ridiculed problematic accompaniment; theater owners became more discriminating in hiring and paying musicians; and audiences came to expect continuous musical accompaniment.

Initially, accompanists, left to their own devices and untrained in their craft, improvised. Therefore the quality of musical accompaniment varied widely. The single most important device in the standardization of film music was the cue sheet, a list of musical selections fitted to the individual film. The most sophisticated of them contained actual excerpts of music timed to fit each scene and cued to screen action to keep the accompanist on track. As early as 1909, Edison studios circulated cue sheets for their films. Other studios, trade publications, and entrepreneurs began doing the same. Musical encyclopedias appeared, containing vast inventories of music, largely culled from the classics of nineteenth-century western European art music and supplemented by original compositions. Encyclopedias like Giuseppi Becce's influential Kinobibliothek (1919) indexed every type of on-screen situation accompanists might face. J. S. Zamecnik (1872–1953) composed theSam Fox Moving Picture Music series (1913–1923). It included not only a generic "Hurry Music," but "Hurry Music (for struggles)", "Hurry Music (for duels)"; and "Hurry Music (for mob or fire scenes)." Even treachery was customized for villains, ruffians, smugglers, or conspirators. Erno Rapee's Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures (1925) offers music for scenes from Abyssinia to Zanzibar (and everything in between). Popular music of the day was also featured in silent film: in illustrated songs during the earliest periods of film exhibition; as ballyhoo blaring from phonographs to lure passersby into cinemas; and in "Follow the Bouncing Ball" sing-alongs, popular in the 1920s. It is not surprising that popular music crossed over into accompaniment.

Much more work needs to be done on the impact of geography (neighborhood vs. downtown settings; the urbanized east coast vs. the less populated western states) and ethnicity and race (the place of folk traditions, ragtime, jazz) on musical accompaniment. By the teens, however, silent film accompaniment had developed into a profession, and the piano emerged as the workhorse of the era. The 1920s saw the development of the mammoth theatrical organ, like the Mighty Wurlitzer, and motion picture orchestras, contracted by the owners of magnificent urban picture palaces. Orchestral scores, music transcribed for the orchestra, developed during the late silent era. Orchestral film scores based on original compositions were rare in the United States, but there are some famous international examples (not all of which, unfortunately, have survived): Camille Saint-Saëns's (1835–1921) L'Assassinat du duc de Guise(1908), Arthur Honegger's (1892–1955)Napoléon (1929), Dmitri Shostakovich's (1906–1975) Novyy Vavilon ( The New Babylon , 1927), Erik Satie's (1866–1925)Entr'acte (1924), and Edmund Meisel's (1894–1930) Bronenosets Potyomkin (Battleship Potemkin , 1925), blamed for causing riots at the German premiere and banned. Most orchestral scores, however, were compiled from existing sources, largely nineteenth-century Western European art music. The first American orchestral score, generally acknowledged as The Birth of a Nation(1915), was a compilation by Joseph Carl Breil (1870–1926) and the film's director, D. W. Griffith, raiding such classics as Richard Wagner's (1813–1883) Ride of the Valkyries , from his opera Die Walkure , and Edvard Grieg'sIn the Hall of the Mountain King , from his Peer Gynt suite no. 1.

Wagnerian opera and Wagner's theory of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork) were early influences on accompanists. Wagner argued that music in opera should not be privileged over other elements and should be composed in accordance with the dramatic needs of the story. Accompanists envisioned film music as performing the same function. Especially influential was Wagner's use of the leitmotif, an identifying musical passage, often a melody, associated through repetition with a particular character, place, emotion, or even abstract idea. Silent film accompanists often used the leitmotif to unify musical accompaniment, and during the period of film's transformation into a narrative form, leitmotifs became an important device for clarifying the story and helping audiences keep track of characters. However, Eisler and Adorno, among other critics, argued that the leitmotif was inappropriate for such short art forms as films.

Spurred by reconstructions in the 1970s of silent film scores by scholar-conductors such as Gillian Anderson and by screenings of the restoration of Abel Gance's Napoléon , silent film has enjoyed a resurgence. The rebirth of the silent film with musical accompaniment has made it possible for audiences today to feel something of the all-encompassing nature of the silent film experience. Original scores have been rescued from oblivion, and new scores have been created. Some of these restorations exist in recorded form and boast the original music:Broken Blossoms (1919), scored by Louis Gottschalk (1864–1934);Metropolis (1927), scored by Gottfried Huppertz; Chelovek s kino-apparatom (The Man with a Movie Camera , 1929), with a recreation of the director Dziga Vertov's (1896–1954) score by the Alloy Orchestra. Other restorations feature newly composed scores: The Wind(1928), scored by Carl Davis; Stachka (Strike , 1925), scored by the Alloy Orchestra; and Sherlock, Jr. (1924), scored by the Clubfoot Orchestra. Giorgio Moroder (b. 1940) used disco in his restoration of Metropolis in 1985. But the most exciting development has been the success of silent screenings with live musical accompaniment at film festivals, in art museums, on college campuses, and sometimes even in renovated silent film theaters.

Copyright © 2015 Advameg

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

Friday, January 09, 2015

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

The Significance or Insignificance of Everything

26 Pictures Will Make You Re-Evaluate Your Entire Existence

1. This is the Earth! This is where you live.

3. Here’s the distance, to scale, between the Earth and the moon. Doesn’t look too far, does it?

4. THINK AGAIN. Inside that distance you can fit every planet in our solar system, nice and neatly.

5. But let’s talk about planets. That little green smudge is North America on Jupiter.

6. And here’s the size of Earth (well, six Earths) compared with Saturn:

7. And just for good measure, here’s what Saturn’s rings would look like if they were around Earth:

8. This right here is a comet. We just landed a probe on one of those bad boys. Here’s what one looks like compared with Los Angeles:

10. Here’s you from the moon:

11. Here’s you from Mars:

12. Here’s you from just behind Saturn’s rings:

13. And here’s you from just beyond Neptune, 4 billion miles away.

14. Let’s step back a bit. Here’s the size of Earth compared with the size of our sun. Terrifying, right?

15. And here’s that same Sun from the surface of Mars:

16. But that’s nothing. Again, as Carl once mused, there are more stars in space than there are grains of sand on every beach on Earth:

17. Which means that there are ones much, much bigger than little wimpy sun. Just look at how tiny and insignificant our sun is:

18. Here’s another look. The biggest star, VY Canis Majoris, is 1,000,000,000 times bigger than our sun:

19. But none of those compares to the size of a galaxy. In fact, if you shrunk the Sun down to the size of a white blood cell and shrunk the Milky Way Galaxy down using the same scale, the Milky Way would be the size of the United States:

20. That’s because the Milky Way Galaxy is huge. This is where you live inside there:

21. But this is all you ever see:

22. But even our galaxy is a little runt compared with some others. Here’s the Milky Way compared to IC 1011, 350 million light years away from Earth:

23. But let’s think bigger. In JUST this picture taken by the Hubble telescope, there are thousands and thousands of galaxies, each containing millions of stars, each with their own planets.

24. Here’s one of the galaxies pictured, UDF 423. This galaxy is 10 BILLION light years away. When you look at this picture, you are looking billions of years into the past.

25. And just keep this in mind — that’s a picture of a very small, small part of the universe. It’s just an insignificant fraction of the night sky.

26. And, you know, it’s pretty safe to assume that there are some black holes out there. Here’s the size of a black hole compared with Earth’s orbit, just to terrify you:

So if you’re ever feeling upset about your favorite show being canceled or the fact that they play Christmas music way too early — just remember…

This is your home.

This is what happens when you zoom out from your home to your solar system.

And this is what happens when you zoom out farther…

And farther…

Keep going…

Just a little bit farther…

Almost there…

And here it is. Here’s everything in the observable universe, and here’s your place in it. Just a tiny little ant in a giant jar.

Monday, November 17, 2014

a great screenwriting quote

Sunday, November 16, 2014

Friday, November 14, 2014

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Thursday, November 06, 2014

A Modern Masterpiece

A piece of Cinema that will stand the test of time.http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1065073/

Wednesday, November 05, 2014

Quote Of The Year.

Monday, November 03, 2014

Herzog on Creativity etc

Werner Herzog on Creativity, Self-Reliance, Making a Living of What You Love, and How to Turn Your Ideas Into Reality

by Maria PopovaHerzog’s insights coalesce into a kind of manifesto for following one’s particular calling, a form of intelligent, irreverent self-help for the modern creative spirit — indeed, even though Herzog is a humanist fully detached from religion, there is a strong spiritual undertone to his wisdom, rooted in what Cronin calls “unadulterated intuition” and spanning everything from what it really means to find your purpose and do what you love to the psychology and practicalities of worrying less about money to the art of living with presence with an age of productivity. As Cronin points out in the introduction, Herzog’s thoughts collected in the book are “a decades-long outpouring, a response to the clarion call, to the fervent requests for guidance.”

And yet in many ways, A Guide for the Perplexed could well have been titled A Guide to the Perplexed, for Herzog is as much a product of his “cumulative humiliations and defeats,” as he himself phrases it, as of his own “chronic perplexity,” to borrow E.B. White’s unforgettable term — Herzog possesses that rare, paradoxical combination of absolute clarity of conviction and wholehearted willingness to inhabit his own inner contradictions, to pursue life’s open-endedness with equal parts focus of vision and nimbleness of navigation.

A certain self-reliance that permeates his films and his mind, a refusal to let the fear of failure inhibit trying — a sensibility the voiceover in the final scene of Herzog’s The Unprecedented Defence of the Fortress Deutschkreuz captures perfectly: “Even a defeat is better than nothing at all.” He tells Cronin:

There is nothing wrong with hardships and obstacles, but everything wrong with not trying.Herzog reflects on failure as a prerequisite for creative mastery:

The bad films have taught me most about filmmaking. Seek out the negative definition. Sit in front of a film and ask yourself, “Given the chance, is this how I would do it?” It’s a never-ending educational experience, a way of discovering in which direction you need to take your own work and ideas.He takes this notion of self-reliance — as he does most things he believes — to an almost religious degree:

I did as much as possible myself; it was an article of faith, a matter of simple human decency to do the dirty work as long as I could… Three things — a phone, computer and car — are all you need to produce films. Even today I still do most things myself. Although at times it would be good if I had more support, I would rather put the money up on the screen instead of adding people to the payroll.Indeed, having grown up without money and earned every penny himself, Herzog considers this self-reliance closely intertwined with the question of financial struggle — a circumstance he always refused to mistake for a fatal roadblock to the creative drive. His wisdom on the subject extends beyond film and applies just as perceptively to almost any field of endeavor in today’s creative landscape:

The best advice I can offer to those heading into the world of film is not to wait for the system to finance your projects and for others to decide your fate. If you can’t afford to make a million-dollar film, raise $10,000 and produce it yourself. That’s all you need to make a feature film these days. Beware of useless, bottom-rung secretarial jobs in film-production companies. Instead, so long as you are able-bodied, head out to where the real world is. Roll up your sleeves and work as a bouncer in a sex club or a warden in a lunatic asylum or a machine operator in a slaughterhouse. Drive a taxi for six months and you’ll have enough money to make a film. Walk on foot, learn languages and a craft or trade that has nothing to do with cinema. Filmmaking — like great literature — must have experience of life at its foundation. Read Conrad or Hemingway and you can tell how much real life is in those books. A lot of what you see in my films isn’t invention; it’s very much life itself, my own life. If you have an image in your head, hold on to it because — as remote as it might seem — at some point you might be able to use it in a film. I have always sought to transform my own experiences and fantasies into cinema.He later revisits the subject even more pointedly:

A natural component of filmmaking is the struggle to find money. It has been an uphill battle my entire working life… If you want to make a film, go make it. I can’t tell you the number of times I have started shooting a film knowing I didn’t have the money to finish it. I meet people everywhere who complain about money; it’s the ingrained nature of too many filmmakers. But it should be clear to everyone that money has always had certain explicit qualities: it’s stupid and cowardly, slow and unimaginative. The circumstances of funding never just appear; you have to create them yourself, then manipulate them for your own ends. This is the very nature and daily toil of filmmaking. If your project has real substance, ultimately the money will follow you like a common cur in the street with its tail between its legs. There is a German proverb: “Der Teufel scheisst immer auf den grössten Haufen” [“The Devil always shits on the biggest heap”]. So start heaping and have faith. Every time you make a film you should be prepared to descend into Hell and wrestle it from the claws of the Devil himself. Prepare yourself: there is never a day without a sucker punch. At the same time, be pragmatic and learn how to develop an understanding of when to abandon an idea. Follow your dreams no matter what, but reconsider if they can’t be realized in certain situations. A project can become a cul-de-sac and your life might slip through your fingers in pursuit of something that can never be realized. Know when to walk away.This question of money parlays into what’s perhaps Herzog’s most urgent and piercing point — a testament to the idea that anything worthwhile takes a long time:

Perseverance has kept me going over the years. Things rarely happen overnight. Filmmakers should be prepared for many years of hard work. The sheer toil can be healthy and exhilarating.Ultimately, this notion of doing what you love is rooted in defining your own success, which often requires the bravery of not buying into the cultural template. Herzog captures this elegantly:

Although for many years I lived hand to mouth — sometimes in semi-poverty — I have lived like a rich man ever since I started making films. Throughout my life I have been able to do what I truly love, which is more valuable than any cash you could throw at me. At a time when friends were establishing themselves by getting university degrees, going into business, building careers and buying houses, I was making films, investing everything back into my work. Money lost, film gained.

Even if I went broke, I wouldn’t be able to sell anything to the highest bidder. What makes me rich is that I am welcomed almost everywhere. I can show up with my films and am offered hospitality, something you could never achieve with money alone… For years I have struggled harder than you can imagine for true liberty, and today am privileged in the way the boss of a huge corporation never will be.

I find the notion of happiness rather strange… It has never been a goal of mine; I just don’t think in those terms.(This calls to mind a line Susan Sontag wrote in her diary in March of 1979: “There is a great deal that either has to be given up or be taken away from you if you are going to succeed in writing a body of work.”)

[...]

I try to give meaning to my existence through my work. That’s a simplified answer, but whether I’m happy or not really doesn’t count for much. I have always enjoyed my work. Maybe “enjoy” isn’t the right word; I love making films, and it means a lot to me that I can work in this profession. I am well aware of the many aspiring filmmakers out there with good ideas who never find a foothold. At the age of fourteen, once I realized filmmaking was an uninvited duty for me, I had no choice but to push on with my projects. Cinema has given me everything, but has also taken everything from me.

Herzog describes his ideation process in almost violent terms, framing the creative act as an inherently ambivalent one, oscillating between creation, destruction, and purging:

The problem isn’t coming up with ideas, it is how to contain the invasion. My ideas are like uninvited guests. They don’t knock on the door; they climb in through the windows like burglars who show up in the middle of the night and make a racket in the kitchen as they raid the fridge. I don’t sit and ponder which one I should deal with first. The one to be wrestled to the floor before all others is the one coming at me with the most vehemence. I have, over the years, developed methods to deal with the invaders as quickly and efficiently as possible, though the burglars never stop coming. You invite a handful of friends for dinner, but the door bursts open and a hundred people are pushing in. You might manage to get rid of them, but from around the corner another fifty appear almost immediately… Finishing a film is like having a great weight lifted from my shoulders. It’s relief, not necessarily happiness. But you relish dealing with these “burglars.” I am glad to be rid of them after making a film or writing a book. The ideas are uninvited guests, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t welcome.

My films come to me very much alive, like dreams, without explanation. I never think about what it all means. I think only about telling a story, and however illogical the images, I let them invade me. An idea comes to me, and then, over a period of time — perhaps while driving or walking — this blurred vision becomes clearer in my mind, pulling itself into focus.In that creative act, Herzog argues, lies the artist’s broader cultural responsibility to continually reinvent the established forms:

[...]

When I write, I sit in front of the computer and pound the keys. I start at the beginning and write fast, leaving out anything that isn’t necessary, aiming at all times for the hard core of the narrative. I can’t write without that urgency. Something is wrong if it takes more than five days to finish a screenplay. A story created this way will always be full of life.

We need images in accordance with our civilization and innermost conditioning, which is why I appreciate any film that searches for novelty, no matter in what direction it moves or what story it tells… The struggle to find unprocessed imagery is never-ending, but it’s our duty to dig like archaeologists and search our violated landscapes. We live in an era when established values are no longer valid, when prodigious discoveries are being made every year, when catastrophes of unbelievable proportions occur weekly. In ancient Greek the word “chaos” means “gaping void” or “yawning emptiness.” The most effective response to the chaos in our lives is the creation of new forms of literature, music, poetry, art and cinema.And yet being preoccupied with form can be limiting — it should emerge from the story organically rather than seek to shape it:

I don’t consciously reflect on aesthetics before making a film because, for me, the story always dictates such things. Of course, aesthetics do sometimes enter unconsciously through the back door, because whether we like it or not our preferences always somehow influence the decisions we make. If I were to think about my handwriting while writing an important letter, the words would become meaningless. When you write a passionate love letter and focus on making sure your longhand is as beautiful as possible, it isn’t going to be much of a love letter. But if you concentrate on the words and emotions, your particular style of longhand – which has nothing to do with the letter per se — will somehow seep in of its own accord. Aesthetics, if they even exist, are to be discovered only once a film has been completed.Herzog doesn’t shy away from touching on the existential:

We can never know what truth really is. The best we can do is approximate… Truth can never be definitively captured or described, though the quest to find answers is what gives meaning to our existence.In one of his most endearingly characteristic proclamations, Herzog tells Cronin why he has never taken vacation:

It would never occur to me… I work steadily and methodically, with great focus. There is never anything frantic about how I do my job; I’m no workaholic. A holiday is a necessity for someone whose work is an unchanged daily routine, but for me everything is constantly fresh and always new. I love what I do, and my life feels like one long vacation.Above all, however, Herzog reveals himself as a rare master of prioritizing presence over productivity:

I work best under pressure, knee-deep in the mud. It helps me concentrate. The truth is I have never been guided by the kind of strict discipline I see in some people, those who get up at five in the morning and jog for an hour. My priorities are elsewhere. I will rearrange my entire day to have a solid meal with friends.Theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss captures Herzog’s singular spirit in the afterword:

The Werner Herzog I have come to know is not the wild man of his press clippings. He is a caring, thoughtful, playful and essentially gentle human being. Possessing a restless mind, with a fertile and creative imagination, he is a man interested in all aspects of the human experience. Self-taught, he is widely read and deeply knowledgeable. I like to think that one of the reasons we enjoy each other’s company is that we both share a deep excitement in the human experience.Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed is a spectacular read in its hefty 600-page totality, offering a rare glimpse of one of the most ravenously imaginative minds of our time. Complement it with other spectacular interviews with David Foster Wallace, Jeanette Winterson, Leonard Cohen, Seth Godin, Dani Shapiro, William Faulkner, Bob Dylan, Adam Phillips, Pablo Picasso, Malcolm Gladwell, and Susan Sontag.

a Singular Experience.

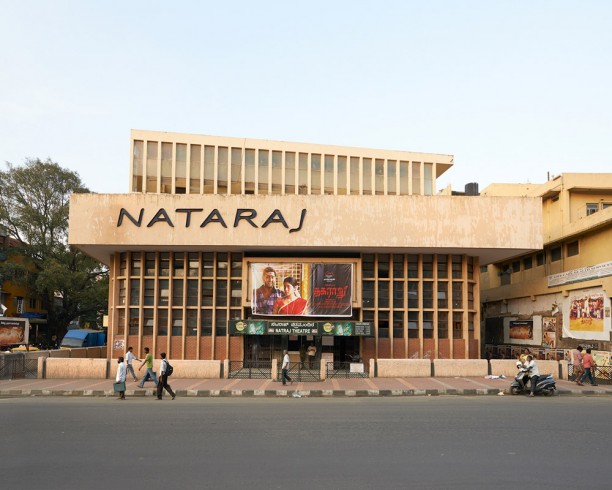

Indian single-screen theatres with plush carpeted halls and art deco exteriors are being threatened with extinction as they are increasingly being converted into multiplexes with attached food courts. Over the past five years, the number of single-screen theatres has dwindled from 13,000 to 10,167, said a report submitted by KPMG, citing figures obtained from the Film Federation of India.

Many of the holdouts, it turns out, are south of the Vindhyas. That's what German photographers Stefanie Zoche and Sabine Haubitz noticed when they travelled through the country in 2010. “We were intrigued by their unusual architectural style that displayed a mixture of western and Indian influences,” said Zoche. “The facades often seem like mock-ups affixed to the building, thus emphasising the architecture’s distinctly theatrical, stage-like character.”

Between 2010 and 2013, Zoche and Haubitz travelled through Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, and noticed many single screen theatres adorned with larger than life cutouts of garlanded movie stars and statues of deities. They compiled their photographs in an exhibition of works titled Hybrid Modernism. Movie Theatres in South India, in Munich.

Here are some of the photographs that will be on display.

Meenakshi, Thirumangalam

Nataraj, Bangalore

New Theatres, Trivandrum

Shanti, Hyderabad

Triveni, Bangalore

Anna Mallai, Madurai

Bharat, Chennai

Sri Bala, Trivandrum

The exhibition is being held in Nusser & Baumgart, Munich, from October 9 to November 15.