Saturday, December 28, 2013

Good Infographics give Interesting Perspective

How to Be an Educated Consumer of Infographics: David Byrne on the Art-Science of Visual Storytelling

by Maria Popova

Cultivating the ability to experience the “geeky rapture” of metaphorical thinking and pattern recognition.

As an appreciator of the art of visual storytelling by way of good information graphics

— an art especially endangered in this golden age of bad infographics

served as linkbait — I was thrilled and honored to be on the advisory

“Brain Trust” for a project by Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist, New Yorker writer, and Scientific American neuroscience blog editor Gareth Cook,

who has set out to highlight the very best infographics produced each

year, online and off. (Disclaimer for the naturally cynical: No money

changed hands.) The Best American Infographics 2013 (public library)

is now out, featuring the finest examples from the past year — spanning

everything from happiness to sports to space to gender politics, and

including a contribution by friend-of-Brain Pickings Wendy MacNaughton — with an introduction by none other than David Byrne. Accompanying each image is an artist statement that explores the data, the choice of visual representation, and why it works.

As an appreciator of the art of visual storytelling by way of good information graphics

— an art especially endangered in this golden age of bad infographics

served as linkbait — I was thrilled and honored to be on the advisory

“Brain Trust” for a project by Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist, New Yorker writer, and Scientific American neuroscience blog editor Gareth Cook,

who has set out to highlight the very best infographics produced each

year, online and off. (Disclaimer for the naturally cynical: No money

changed hands.) The Best American Infographics 2013 (public library)

is now out, featuring the finest examples from the past year — spanning

everything from happiness to sports to space to gender politics, and

including a contribution by friend-of-Brain Pickings Wendy MacNaughton — with an introduction by none other than David Byrne. Accompanying each image is an artist statement that explores the data, the choice of visual representation, and why it works.Byrne, who knows a thing or two about creativity and has himself produced some delightfully existential infographics, writes:

The very best [infographics] engender and facilitate an insight by visual means — allow us to grasp some relationship quickly and easily that otherwise would take many pages and illustrations and tables to convey. Insight seems to happen most often when data sets are crossed in the design of the piece — when we can quickly see the effects on something over time, for example, or view how factors like income, race, geography, or diet might affect other data. When that happens, there’s an instant “Aha!”…Byrne addresses the healthy skepticism many of us harbor towards the universal potency of infographics, reminding us that the medium is not the message — the message is the message:

A good infographic … is — again — elegant, efficient, and accurate. But do they matter? Are infographics just things to liven up a dull page of type or the front page of USA Today? Well, yes, they do matter. We know that charts and figures can be used to support almost any argument. . . . Bad infographics are deadly!And, indeed, at the heart of the aspiration to cultivate a kind of visual literacy so critical for modern communication. Here are a few favorite pieces from the book that embody that ideal of intelligent elegance and beautiful revelation of truth:

One would hope that we could educate ourselves to be able to spot the evil infographics that are being used to manipulate us, or that are being used to hide important patterns and information. Ideally, an educated consumer of infographics might develop some sort of infographic bullshit detector that would beep when told how the trickle-down economic effect justifies fracking, for example. It’s not easy, as one can be seduced relatively easily by colors, diagrams and funny writing.

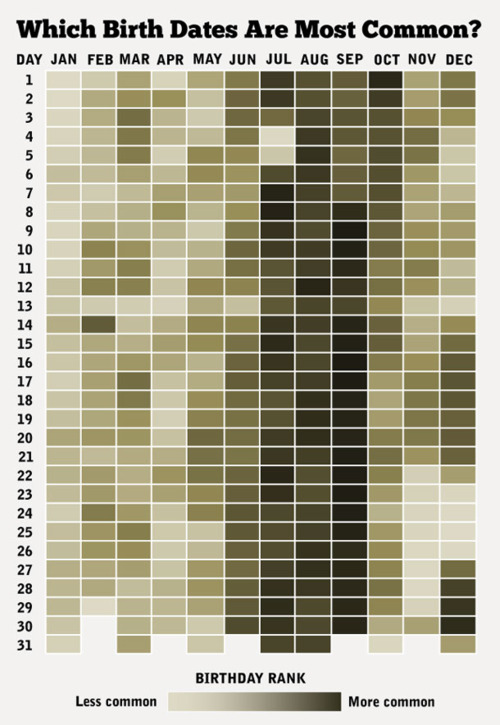

The days of the year, ranked by the number of babies born on each day in the United States (Matt Stiles, NPR data journalist)

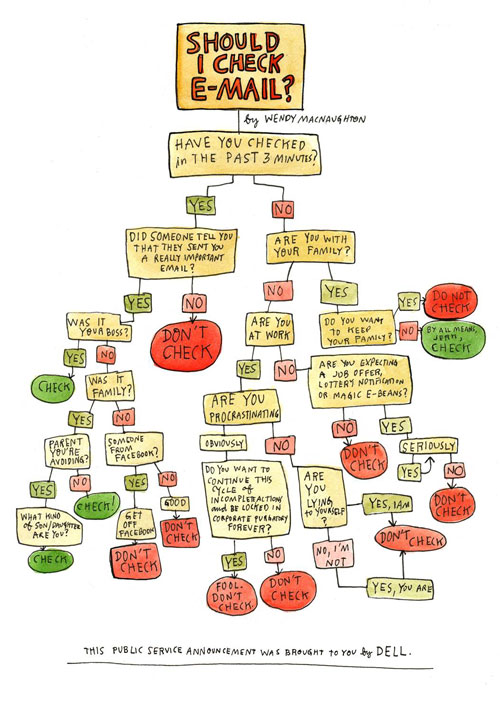

Flowcharts [are] a form of poetry. And poetry is its own reward.Indeed, flowcharts have a singular way of living at the intersection of the pragmatic and the existential:

A handy flowchart to help you decide if you should check your email. (Wendy MacNaughton, independent illustrator, for Forbes)

Just ask yourself one question. (Gustavo Vieira Dias, creative director of DDB Tribal Vienna)

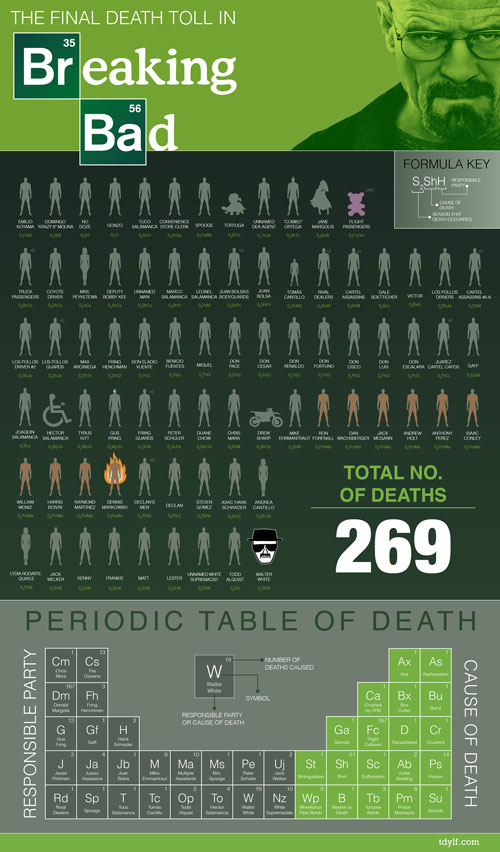

All of the deaths in the first fifty-four episodes of AMC's ‘Breaking Bad,’ with each deceased character represented by a faux chemical formula indicating when he or she died, how they died, and who killed them. (John D. LaRue)

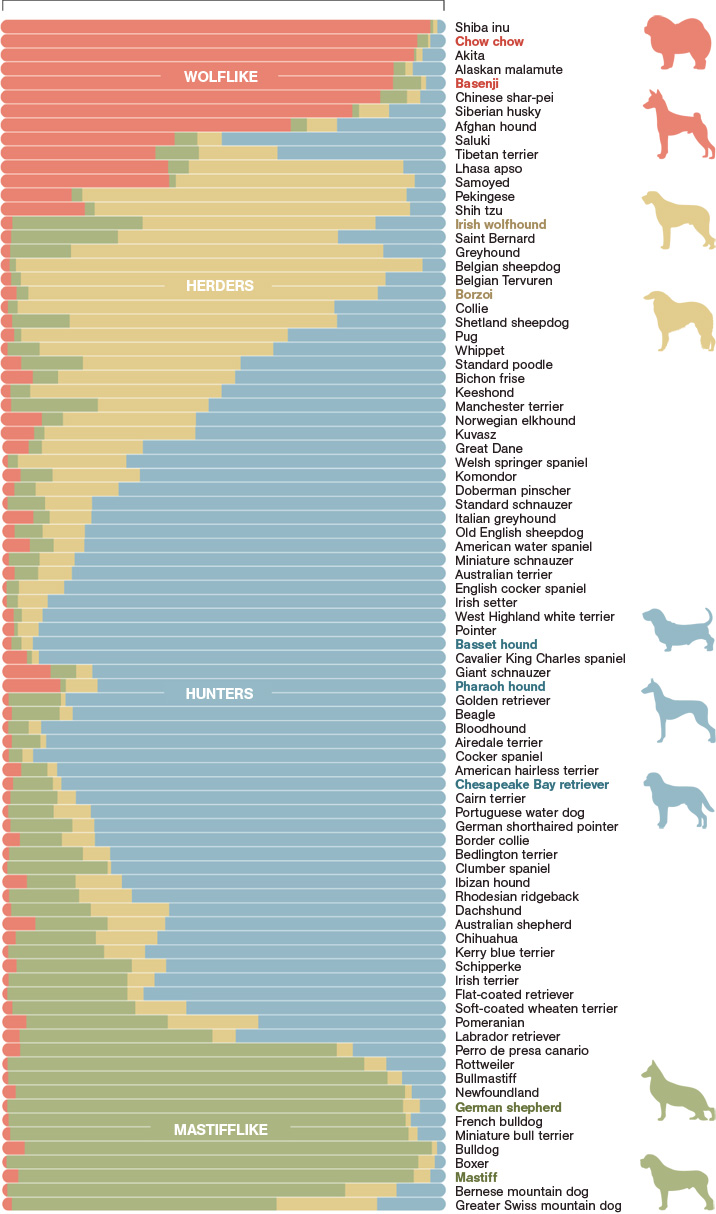

Analyzing the DNA of 85 dog breeds, scientists found that genetic similarities clustered them into four broad categories. The groupings reveal how breeders have recombined ancestral stock to create new breeds; a few still carry many wolflike genes. Researchers named the groups for a distinguishing trait in the breeds dominating the clusters, though not every dog necessarily shows that trait. The length of the colored bars in a breed’s genetic profile shows how much of the dog’s DNA falls into each category. (John Tomanio, senior graphics editor, National Geographic)

‘Flow map’ of travel in New York City derived from the locations of tweets tagged with the locations of their senders. The starting and ending points of each trip come from a pair of geotagged tweets by the same person, and the path in between is an estimate, routed along the densest corridor of other people's geotagged tweets. (Eric Fischer, artist in residence at the Exploratorium in San Francisco)

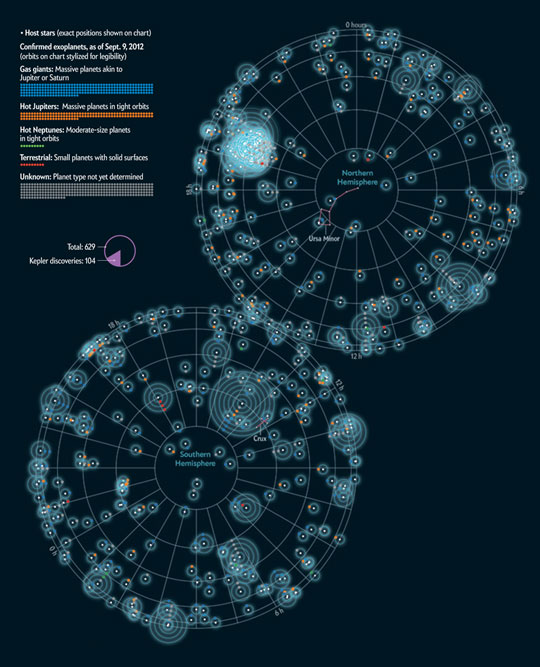

All of the planets discovered outside the Solar System. (Jan Willem Tulp, freelance information designer, for Scientific American)

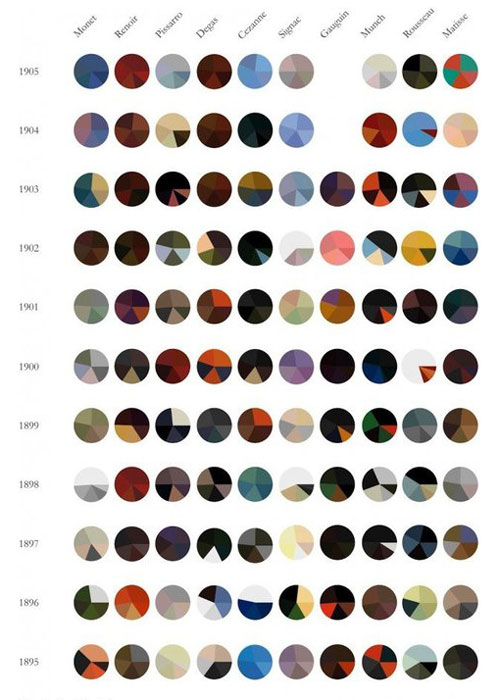

A revolution in color over ten extraordinary years in art history. Each pie chart represents an individual painting, with the five most prominent colors shown proportionally. (Arthur Buxton)

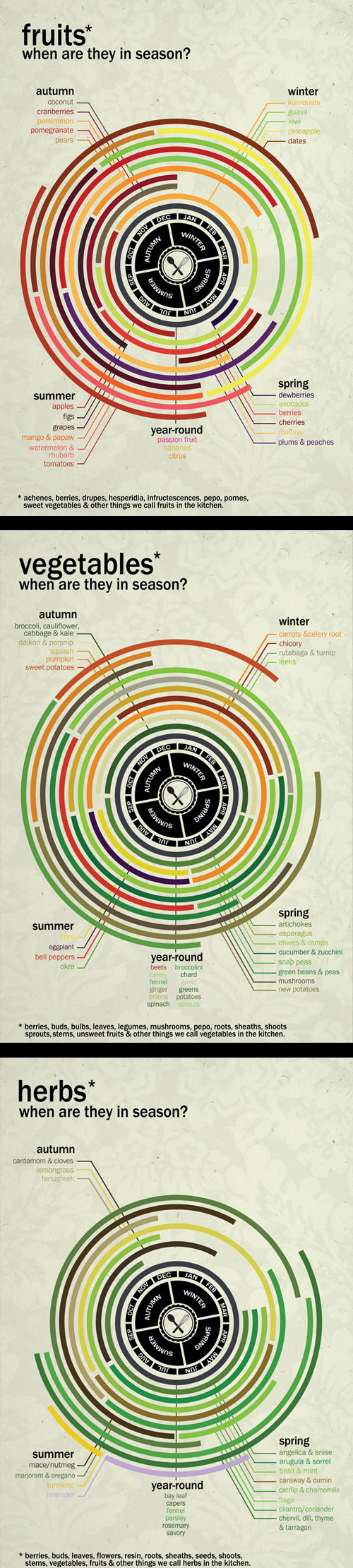

The availability of produce in the northern hemisphere by month and season. (Russell van Kraayenburg)

We have an inbuilt ability to manipulate visual metaphors in ways we cannot do with the things and concepts they stand for — to use them as malleable, conceptual Tetris blocks or modeling clay that we can more easily squeeze, stack, and reorder. And then — whammo! — a pattern emerges, and we’ve arrived someplace we would never have gotten by any other means.Complement The Best American Infographics 2013 with Nathan Yau’s indispensable guide to telling stories with data and Taschen’s scrumptious showcase of the best information graphics from around the w

Monday, December 16, 2013

Thursday, December 05, 2013

The Temple Conolly Review of Avakai Biryani

Avakai Biryani

Filed under: Tollywood by Temple Connolly — 6 Comments

October 15, 2010

Akbar Kalam is a Muslim, an auto driver, a student and an orphan. He is caught between worlds and striving to make his way. He lives in a charity cottage, works for Master-ji the local big-wig, and dreams of getting his B.Comm despite failing his exams several times. His exam record is a running joke in Devarakonda.

Spirited graduate Lakshmi (Bindhu Madhavi) and her Brahmin family arrive in Devarakonda needing to start over after losing their fortune. Lakshmi starts making and selling her signature avakai and tries to get her father motivated to get back on his feet.

They both belong and yet they don’t, both making the best of what they have, and so a friendship grows. Lakshmi agrees to tutor Akbar and he helps her fend off unwanted attention from Babar – a leader in the Muslim community and a man with a predilection for satin pajamas. I seriously doubt Akbar was failing only because of his English skills, but Lakshmi doesn’t give up on him as quickly as I would have!

The handling of diversity in the Devarakonda population seemed to me to be very well done. I don’t have the expertise to comment on the reality of this portrayal but can say that as a narrative device it works extremely well. While religion does draw a line through the community, it is depicted as one among many divisions in this village. There are lines of caste, creed, financial status, education and of relationships. Characters cross these lines and back again as the business of making a living and getting the chores done is uppermost and there are few moments of speechifying. The lines of division become much sharper when marriage is in question, and that underpins much of the story.

We see where this is heading a long time before Lakshmi and particularly Akbar seem to. I have my doubts as to how long a boy and girl can hide any “friendship” in a small community, but their roaming around does give Kuruvilla the chance to show the beauty of rural Andhra Pradesh. The growing relationship seems natural and unforced and is not based on any love-at-first-sight or stalking. He calls her Avakai (or as my subtitles have it, Pickles), referring to her identity but also to her hopes for building a future. Their love grows from knowing and valuing each other.

The obligatory spanner in the works comes from the ongoing tension with Babar which is fuelled by testosterone, religion and politics. Babar tries to use religion as a lever to force Akbar to back down but fails as the hero decides to do what’s right for the whole village in a scene with shades of SRK in Swades.

Threats are made, scuffles take place and things boil over between the two men. There is only one way for honour to be satisfied. By an auto race around the village! I know some people rolled their eyes at this episode but it rang true to me. I just rolled my eyes at the sheer stupidity and very boyish behaviour. Oh and it allowed Kamal Kamaraju to get his shirt off, which I suspect is a legal obligation for any Telugu film hero. And there was an explosion, which may also be a compulsory element as well as a machete flourish.

Having established his right to stay in the village, managed a scheme to bring mains water to Devarakonda and finally passed his exams, Akbar has one last obstacle – getting Lakshmi. Despite acknowledging his help and decency towards them all, her family refuse to consider him as a suitor because of his religion and because of his limited prospects. Akbar and Lakshmi simply go their separate ways. Her family pressure is too much to withstand, and he has no family to offer them shelter or support.

This is a total spoiler so stop now if you don’t want to know how it all ends.

Akbar throws himself into work, builds on his success in politics and becomes a respected member of the local council. Two years on, Lakshmi’s father hears him speak at a political meeting and apparently undergoes a change of heart on hearing successful Akbar still speak of Lakshmi with feeling. She sends Akbar a jar of pickles with a note asking him to meet her. He looks radiant with joy as he realises the note is from Lakshmi and she is doing well.

They meet, she pretends not to mind his dodgy moustache, and then hands him a wedding card. There are tears on both sides before he sees the card is for their own wedding and that’s it. Happy ever after time. I expected a bit of anger from Akbar at this cruel trick but I think it’s already clear who really wears the pants in this relationship.

Surprisingly I don’t think this ending was either a cop out or disgraceful behaviour by her dad. Neither Akbar nor Lakshmi had the resources to throw family aside and go it alone. I can imagine it would be hard to marry off an opinionated educated girl especially if people began to talk about her relationship with the Muslim boy. She may not have had many takers after all. And why wouldn’t career success influence a father who has experienced losing everything and seeing his family suffer? Anyway I liked the resolution. No fireworks, just happiness and relief. I really liked that the girl was fully involved in choosing her own path and went in with eyes wide open.

The cinematography is beautiful. The colours are lush and welcoming; the village is dilapidated and picturesque. Kuruvilla paces the story well and doesn’t resort to the predictable speeches and characters. Both leads look good but not too glamorous. Their dancing is not brilliant but it seems entirely suited to the characters so their emotions were the real focus, not fancy footwork. The music blends with the story and the songs are used well, with matching choreography from Prem Rakshith

All the support cast are effective and resist descending into total caricatures. The actors who play Akbar’s best friends are great fun, particularly Praneeth as Sondu who is the embodiment of the fiery spirited party boy that loves his booze, good times and his mates.

I have said before that romance is my least favourite genre. Often I find the plots too silly and the characters poorly acted or insufficiently interesting for me to care about how they are going to navigate the ridiculous story. Avakai Biryani is a successful film for me. It has substance and some thoughtful commentary in addition to charm and pretty visuals. The leads give good solid performances, and the supporting performers are excellent. I give this 4 stars! Temple (Heather will post a film review soon. Don’t panic!)

Wednesday, December 04, 2013

Avakai Biryani: Filmowe zaduszki AD 2013: 'Ko Ante Koti' & 'Memori...

Avakai Biryani: Filmowe zaduszki AD 2013: 'Ko Ante Koti' & 'Memori...: Jak to już stało się moją doroczną tradycją, w listopadzie po raz kolejny przystąpiłam do filmowych 'wypominek', czyli ekranowych s...

On Malayalam Cinema - Nisha Susan

The Pot that Broke Below a Hundred Other Pots

If you have the option of picking from among half a dozen cinematic traditions, why would anyone choose to look for romance in Malayalam cinema – the most determinedly unromantic of them all?

By Nisha Susan | Grist Media – Mon 2 Dec, 2013

Towards the middle of Aaraam Thampuran, a 1997 movie with Malayali actor Mohanlal in the lead, the hostile villagers are steadily awakened to the true ‘noble’ roots of the bad man who has bought the big house. The villagers – and the audience – are given broad hints that he isn’t just the goonda from Bombay they thought he was. It is in the nature of the movies the Malayalam industry was making in the late 1990s that Jagan (Mohanlal) was revealed to be not just a secret aristocrat; he was a secret aristocrat from the village who has now returned to his rightful place. The ‘Lost Heir’ is not a new trope, but hoary as it is, it can still be satisfying.

Unfortunately, what was memorable for me about the Lost Heir in this movie was something that happens in the middle of the film. Someone from the city comes to meet Jagan for prosaic business. The moment he sees Jagan the man is wreathed in confused smiles. “Aren’t you the Jagan who ran an art journal in Delhi?” Mohanlal the actor tries to look modest and yet cosmopolitan but looks like he is suppressing giggles instead. The establishing of Jagan the violent thug as a Delhi gallery owner, a classical musician in Gwalior, a jet-setting aesthete, is done with this swift exchange, followed by the arrival of his long-term city girlfriend who offers to cheer him up by taking him to any of his favourite places. “London? Paris? Vienna?” she trills alongside being ‘chulbuli’ – the pan-India cinematic mutation of female vivaciousness, which is usually represented as chihuahua on speed.

As an 18-year-old, Aaraam Thampuran made me wince for days. “Ningal Alle Delhi yile aaa art journal…? (Aren’t you…? The one who ran the art journal in Delhi?)” over the years became my shorthand for unconvincing, name-dropping arty characters in movies. It embarrassed me deeply. (Perversely, Suresh Gopi, hero of Lelam – also from 1997 – resorting to Yiddish in the middle of a trademark tirade against the villains, ‘You schmuck’, only made me fall about laughing.)

Over the years, I’ve also become a little grudging of the long explanation (such as the one in the above paragraph) I must make for this reference when I’m around someone who does not watch Malayalam cinema.

You’d think I’d have options other than Malayalam cinema for bonding in this movie-mad nation. My family was addicted to movie-watching in five different languages and thought it perfectly unremarkable. What was a bit unusual was that my paternal grandparents owned a movie theatre in the village for a while. We were packed off, all of us cousins, resident and visiting, to watch whatever raunchy 1980s Malayalam movie was running in the afternoon, to keep us off the streets and out of the pond or the local timber mill where the elephants were diligently working.

For a while, after the afternoon show, I’d race out to the back of the theatre hoping to catch the actors, since I’d somehow imagined that they were just behind the screen. No one worried about what we were watching. Movie-watching was completely respectable in that household. My paternal grandparents even offered to take my mother to the movies to distract her from labour pains when she was about to give birth to me. I suspect if the gimlet eye of her own mother (who was convinced that all in-laws are villains unless proven otherwise) hadn’t been on her, my mother would have gone gamely to the matinée. To see something by Sukumaran, probably, or MG Soman. Soman once turned up in the village to promote his movie and all of us grandchildren were gobsmacked seeing our house surrounded by hundreds and hundreds of fans. We got nowhere near the star, of course. But the stars seemed very close, so close that I’ve a false memory of staring into the sky after being told the breaking news that the action star Jayan had fallen off a helicopter during a stunt and died. An utterly false memory, because when Jayan with the Errol Flynn moustache died, I was just a year old.

After my parents left Kerala, first for Nigeria and then to Oman, their movie addiction continued. They watched British and American cinema (though I don’t think they discovered Nigeria’s own.) There is also some family legend that when we were robbed to the last spoon in Nigeria, my parents were left only with a trunk full of movies which they sold to finance my father’s visa to Oman.

Later, through their decades in Oman, my parents were always members of the local video library in whatever tiny town on the Batinah coast they were stuck in, and watched three or four movies every week. They watched Malayalam, Tamizh, Hindi, Telugu movies and of course, Hollywood. In the summers when my brother and I visited them from India, my mother stocked up the fridge with treats and piled up the videos that she had enjoyed all year.

I was more than happy to plunge into the crazy comedies that she usually picked, particularly because in Bangalore, where I went to school, my movie viewing was rather virtuous. The Kannada movie every Saturday evening (Rajkumar as Krishna, Rajkumar as James Bond) and something horribly cheerful in Hindi on Sunday evenings. The only Malayalam movies I caught on television were worthy national award winners like Adoor Gopalakrishnan and G. Aravindan works which, to my pre-teen self, were parodies of long silences and bewildering ambiguities.

Superficially, I went through the same rites of passage as everyone else of my generation in Indian cities, graduating from Amitabh Bachchan to Shah Rukh Khan, or from Kamal Hasan to Madhavan. But I had no clue what my friend Vinaya was talking about when she says she first understood sexual desire after seeing Amitabh Bachchan in Deewar, or my friend Paro, to whom Shah Rukh means pure love. I found romance in the crevices of Malayalam cinema.

Hollywood was where people tongue-kissed, the same fictional universe as Mills & Boons, where people had no parents and could do anything. Hindi movies had even more baffling people: those who knotted jaunty handkerchiefs around their necks and played pianos. Telugu movies had people doing aerobic routines en masse on shiny disco floors under shiny disco balls. Malayalam movies had Malayalis, who, like me, couldn’t dance, were uncool but snippy. At best, they could look over mountain vistas while clad in knotted sweaters. Mostly, they couldn’t do that either without making fun of themselves.

The climax of one of my favourite movies Mithunam (plot: Sethumadhavan wants to start a biscuit factory but everyone wants a bribe) works around a disastrous romantic getaway to the hills and the hero’s tirade against his long-term girlfriend’s cinematic expectations of love. I don’t know why Sethumadhavan bothered. The entire movie was puncturing romance in cinema. Here is Sethumadhavan and buddy outside his girlfriend’s house planning the quick elopement. Buddy peeps over the bushes and spies a teenaged girl sweeping the courtyard. Buddy: Is this thirteen-year-old the one you said you have been in love with for the last sixteen years? Later, as they are carrying away the girlfriend rolled up in a mat, Sethumadhavan spots his girlfriend’s older brother. Sethu: Oh my god, it’s her brother! Buddy: Is that the elder brother of the burden we are currently bearing?

Why would something so fundamentally anti-romance fizz in my veins?

I don’t want you to think these movies were charmless or nihilistic. They did have the lover who quotes a passage from the Song of Songs (“let us go out early to the vineyards and see whether the vines have budded, whether the grape blossoms have opened and the pomegranates are in bloom. There I will give you my love.”); the woman who scams her neighbour and convinces him that her ‘foreign’ dark glasses give her x-ray vision to see through his clothes; the woman who goes from Bangalore to the funeral of her mercurial lover and finds the identical twin he’d kept in Kerala as a prank; the young wife of the old brahmin who is smeared with the face-paint of her Kathakali dancer lover.

It wasn’t that Malayalam cinema was staid either. I didn’t need to see Silk Smitha to be shocked. Why bother when there was Mammooty in an eye-poppingly tight swimsuit, or heroines in gratuitous towel-wearing-and-playfully-fighting-in-bed scenes? Why bother with item numbers when the worldliness of the script could titillate so much more? Take this scene: aunt of heroine tells her that she’d better marry suitable boy aunt has picked out or else. Heroine refuses. The very next scene: post-coital aunt in bed with suitable boy telling him to not to worry, the heroine will come around or she will be made to.

Or take the mildly arty film I caught one afternoon in which the orphan from the city who is trying hard not to scandalise the village inadvertently (when she is sitting at the stoop of the house she remembers to keep her legs covered entirely under long skirts) and is instead surprised by her first kiss – in broad daylight with a casualness and lack of soothing soundtrack.

It took me years to understand that the romance Malayalam movies offered me lay elsewhere. Somehow it had leaked out of everything from the Keystone Kop comedy of Nadodikkattu to Mithunam, to the political satire of Sandhesam into the real world. Romance lay in the particular comic timing of Malayalis: the deadpan delivery, the unexpected terms of reference, the particular rhythms of speech. Though I speak, read and write Malayalam, I’ve lived very little in Kerala and have no formal understanding of its literature. I don’t know enough to decide whether the Malayali men of my generation speak like the movies or the movies speak like them.

All I know is that a certain rhythm of speech will get me every time because it reminds me of a long history of movies: one collapsing on another with a clang and a crash like the school cycle stand when my friend Nishad came downhill and lost control of his new Hero Ranger. No, to be accurate they fall like the one pot that broke in the beginning of the 1994 movie Thenmavin Kombath (elderly lady to Manikyan: Are you saying the police came because you broke one pot at the market? Manikyan: Well, no, that was probably because the pot I broke had a few hundred pots above it.)

Sometimes it’s a just a silly memory. In my family, we just need to hold up a chilli with a solemn face to crack each other up. It evokes the matriarch of Melaparambil Aanveedu handing her three unmarried sons and her unmarried brother-in-law chillies like swords to take into battle, because gruel and chillies were the only items on the menu henceforth, because she had no plans to cook ever again.

Mostly, though, it’s not just deplorable nostalgia. My favourite exchanges were always the ones that went from grouchy to absurd in three sentences, usually written by the diamond-sharp (writer, actor, director) Sreenivasan. Observe my most beloved sequence ever in Sandhesam, a movie about two brothers who are lowly but rabid members of rival political parties. It’s lunchtime and each brother tries to turn their newly retired father (freshly arrived in Kerala from a lifetime posting in Tamil Nadu and hence, the movie implies, an innocent abroad) towards their side. Impassioned one-upmanship careens from the IMF to the gold standard to the devaluation of the rupee to the puppet government in Nicaragua, the collapse of Hungary, and ends with the Communist brother (Sreenivasan) sternly warning the Congress brother: “Polandine patti oraksharam nee parayaruthu (Don’t you dare say a word about Poland).”

I have my share of affection for Dharmendra and Amitabh Bachchan in Chupke Chupke and I smile politely at people who rave about Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron. So polite that I don’t even think to myself: brother, what would you do if you watched Narendran Makan Jayakanthan Vaka, a surreal, serene comedy that spans the 24 hours of a man (non-resident Malayali freshly arrived in Kerala from Tamil Nadu and hence again, the movie implies, an innocent abroad) trying to get compensation for the property that his father lost to the Kannur Airport? What would happen is that your brains would leak out of your ears.

But I don’t say that. My pleasures remain private.

When I was 24, I was stuck on a project for weeks at a stretch with a pothead designer. He had nothing to recommend him except his general sweetness and the facsimile of Malayalam movie comic timing that I now realise I’m fatally attracted to. The rest of the package – the distrust of emotion, the moping, the languor – I could do without. I did do without.

Years later we bumped into each other on the street. I was hanging out with N, a Malayali friend who speaks less Malayalam than I do and for whom, therefore, Malayalam humor is only accessible as a bittersweet groupie. Obviously, in his presence I like to perform quick acts of Malayaliness. Like teasing a true-blue Malayali in Malayalam. Acquired as my register is from movies which give female characters next to nothing to do or say, my ‘material’ (as the stand-ups say) is necessarily laddish. I’m inclined to say shavam for effect. (What? It means corpse and don’t ask me why it’s a swearword). I’m inclined to say shavam, kundam, myru (corpse, spear, pubic hair) not ‘sheeee’ or ‘cheee’ as ladies ought to.

So there I was doing my number and my lost-lost crush put up with it for a while. He was silent as the tomb as he had always been. When I teased him about something obscure he waited two beats and then said, “oho.” Then another beat. N and I stared. “Vitt-uh.” he completed deadpan. I was slain. Living across the border from Kerala, N and I have to wait for years before there is any context for anyone unleashing that familiar, contemptuous Malayalization of the English word ‘wit’. For N and me, it was better than sex.

* * *

The Malayalam folk rock band Avial has made some inroads into the world of my Malayali and non-Malayali friends in the last few years. Though I like some of their tracks I have an irrational suspicion, a Scrooge-ish resistance to their trendiness among some people I knew.

As Malayalam cinema becomes more globalised, has more globalised faces, bodies and features, embarrassments such as whirling dervishes on Kozhikode beach (oh Ustad Hotel, how I loved you for the first twenty minutes with your screen-full of cute hijabi girls before you pulled your faux-Sufi nonsense on me) I’m rendered more and more cranky.

I saw Neelakasham Pachakadal Chuvanna Bhoomi and pulled my hair out in clumps. The cute-boy protagonists are riding through the country on fancy motorcycles, okay. They are being serenaded through said south Indian countryside by piggybacking rollerskaters, er…okay. But the voice-over in half-Malayalam and half-English made me cry: “They say the road has answers for everything. Enalum enyike chothiyangal ilayaranu. I was confused on (sic) identity, politics, happiness, freedom. The only thing I was always sure about ente vidhi ente thirumanangalanu and I chose to be with her.” This movie may well be somebody’s Dil Chahta Hai but boy, does it look like one giant Delhiyile art journal.

It isn’t nostalgia that makes me resistant to the smart, new movies of Malayalam cinema. It is the knowledge that I may have to wait a long cinematic lifetime before smart patter comes back, absurdity comes back, uncool comes back. For a brief while, my neurotic, shifty sense of humor and desire for self-deprecating romance was in sync with what was on screen. For a brief while, I possessed cinema aglow with men who were not dudes, who were utter failures at being dudes, who broke your heart permanently with their undude-ishness. Their toes were almost always making circles in the sand while the heroines stared bemused at them. When the scripts required them to be jet-setters they looked giggly.

The beginning of the end came with a swathe of macho movies with two-word English titles: The King, The Commissioner (and to our recent horror, a sequel called The King & The Commissioner). The soft, dysfunctional heroes I loved were suddenly bursting out of tight uniforms or uniform-like office gear. Their mouths were filled with tooth-cracking, breathless rants about the evils of the nation and the worse evils of forward women in trousers who have careers.

For a long while I stopped watching Malayalam movies. I switched to Tamizh where luckily the age of the sexy, dysfunctional hero was just around the corner.

My baby cousin Prem (well fine, he is a giant six-foot person now) is my current source for the best things from Kerala. I trust, for instance, that he will not peddle two random boys on bikes surrounded by roller-skaters with a portentous voice-over to me. After all, when I started researching Malayali nurses he blew my mind by making me watch 22 Female Kottayam, the adventures of the bobbitising nurse Teresa Abraham. So when he sends me a link saying watch this, I watch it. Even if it is a video of Avial’s song from the soundtrack of the Malayalam movie Salt N’ Pepper. I’d mildly enjoyed the movie for its slightly stoned and runaway plot about two not-so-young people finding love through cooking.

Revisiting the music video didn’t seem like too much fun. Here were the dudes jumping around doing their dude thing singing in a flood-lit set (with motorcycles and extraneous sofas) about Ayyapan the elephant thief, Ayyapan the yam thief. Why should I care, I thought in my familiar Scrooge-ish way.

And then I saw it. On the dudes’ t-shirts was the almost-impossible-to-read line: “Polandinepattioraksharam nee parayaruthu.”

I won’t say a word about Poland if you won’t.

Nisha Susan is an editor for Yahoo! Originals and the women’s zine The Ladies Finger. Her fiction has been published by n+1 magazine, Caravan, Out of Print, Pratilipi, Penguin and Zubaan, and she is currently working on her first book.

The Temple Connolly Review of Ko Antey Koti.

Ko Antey Koti

Filed under: Tollywood by Temple Connolly — Leave a comment

December 3, 2013

The vintage heist genre has been reinvigorated by the likes of Steven Soderbergh, Guy Ritchie, Choi Dong-Hoon, Abhinay Dey and Akshat Verma. Anish Kuruvilla adds his own stamp with Ko Antey Koti.

The rules of heist films require that the target must be audacious and the very elaborate plan must rely on split second timing and specialist skills. There will be loads of characters with unique talents and many of them are disposable. There must be at least one despicable villain who must have a grievance with the hero. Subplots abound, as do betrayals. Add family or romantic tensions, a heap of flashbacks, and you’ve got the basics.

Sharwanand is one of my least favourite Telugu actors but I will grudgingly admit he is improving a bit. He was terrible in the tedious Gamyam (I refuse to let Heather give me my DVD back), he had moments of adequacy in Prasthanam, and he manages to be convincing as Vamsi most of the time. Vamsi seems to be a criminal through lack of motivation to do anything else rather than any commitment to being an outlaw. Sharwanand is perfectly fine in conversational or romantic scenes. When he has to convey powerful emotions he seems to pause for an instant before deciding what expression to use, and so he seems stilted. Having said that, he has good rapport with Priya Anand and their scenes flow very nicely. He generally plays Vamsi as grumpy and whiny, so his lighter moments with Sathya and the troupe or with Chitti and PC are quite endearing.

There are few Indian cinema leading ladies that look as though they really could travel by public transport or know their way around a kitchen. Go on. Picture Katrina Kaif catching the 86 tram. Priya Anand has a freshness and natural vivacity that plays to great effect in this role. Sathya is a slightly unusual heroine by Telugu film standards as she has a brain and uses it. She is voluble and a bit too inclined to Do Good through street theatre, but her chatter is often a tactic to bulldoze over any objections.

People find themselves doing as she asks even though they had no intention of agreeing. I’m not convinced that her dance students would learn much, but the kids seemed to enjoy leaping about with her. Sathya’s determination to lead a socially responsible life makes sense when more of her family story emerges. Her relationship with Vamsi is complicated by a shared connection neither knows of. The past is hard to escape, even when it isn’t your own.

The late Srihari is the criminal mastermind, Maya. Maya is crude and has no love for anything except money. He uses people to get what he wants and has no compunction about terminating an association. Srihari dominates the confrontational scenes with total ease. This works quite well considering Vamsi and the other sidekicks are supposed to be relatively unthreatening. I questioned why he would hire so many idiots but all became clear. Srihari gives Maya a plausible charm, as long as you don’t look too closely at the calculating eyes. And you forgive the dodgy wig. It’s another in a long line of bellowing patriarchal figures for Srihari but he brings it and Maya is a despicable man.

The romance between Sathya and Vamsi is developed in ways that are credible yet still entertaining. One of the things I liked most about Kuruvilla’s Avakai Biryani was the way relationships grew and were strengthened through shared small moments, and he is similarly detailed in this story. Even the romantic sideplot with Chitti and a prostitute was funny and a little touching. Sathya helps Vamsi because he needs help, not because she is smitten with insta-love for The Hero. She chooses to be a happy and good-natured girl, and her open heart allows Vamsi the opportunity to see himself as he could be if he made different choices.

Anish Kuruvilla added some fun flourishes. Sparks literally fly when the couple kiss and no filmi cliché is overlooked as they prance through a gloriously pretty montage. Vamsi acts the part of an actor and proposes on stage, being more honest in his pretence than as himself.

Sex is treated in a non-scurrilous manner. Sathya was actually wearing more fabric when swaddled in her bedsheets than in any of her sarees. I cheer for a heroine who doesn’t have to die immediately after she sleeps with her boyfriend, and it is refreshing to see consensual and mutual attraction between the lead characters. I also liked that Vamsi acknowledged Sathya’s right to have some input into a critical decision. It wasn’t a grand speech, but a moment that showed their pragmatism and trust in each other.

Cinematographers Erukulla Rakesh and Naveen Yadav captured the different worlds the characters inhabit. The light is harsher and the shadows deeper in Maya’s criminal milieu, places full of twists and turns, the suggestion of hidden watchers. Vamsi and Sathya fall in love in a much more colourful and soft setting, a rural paradise and open skies that give space for dreams. The final scenes are in an arid landscape as everything is laid bare and no secrets remain. I really liked the styling of the seedy nightclubs, the squalid apartments, the activity humming through the street scenes. There is a strong sense of place and a modern feel to the sharp edits and angles.

The abundance of incidental characters can mean that characterisations are sketchy. Gluttonous PC (Nishal) and scrawny, one-eyed Chitti (Lakshman) play it as broad as can be. There is no subtlety. Perhaps because of my allergy to Indian film comedy, I was not even slightly sad to see some sidekicks bite the dust early on. If someone minor has a tragic backstory or is the butt of all jokes, do not bet on that character making it to intermission. Corrupt policeman Ranjit Kumar (Vinay Verma) is on the trail of the stolen goods and has his own grudge against Vamsi and Maya. He is a type rather than a realistic or subtle interpretation, but that wasn’t a drawback. The fun of this genre is the guessing and double-guessing rather than delving into a layered psyche.

The songs are used very well and to an extent they amplify characters’ inner lives. I was not overly impressed by the picturesque wandering and montages – I like a big dance number or two. Shakti Kanth has chosen to use different styles of music that match with the action and help build the atmosphere.

It’s refreshing to see a boys own adventure have interesting female characters. There is a little more realism to some of the relationships and there are some gorgeous visuals. The comedy sidekicks are neither funny nor interesting so I tuned out while they were doing their thing. I’m still not convinced by Sharwanand but Priya Anand and Srihari are great. Kuruvilla juggles the elaborate setup and flashbacks in a structured way that feels dynamic but is still logical so I never felt I lost the internal timeline. He’s a realist, especially about traffic and human nature. Well worth a look, especially if you like a more urban gritty thriller. 3 ½ stars!

http://cinemachaat.com/2013/12/03/ko-antey-koti/

EXPERIMENTS WITH LIGHT

via Facebook https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10152116279424343&set=a.224945474342.165714.678474342&type=1

Tuesday, December 03, 2013

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)