The Hemingway You Didn’t Know: Papa’s Adventures

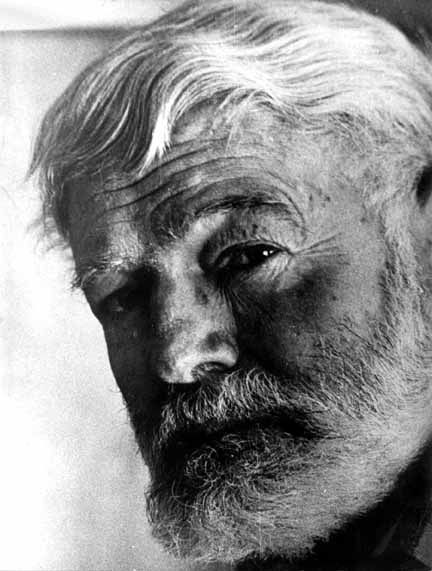

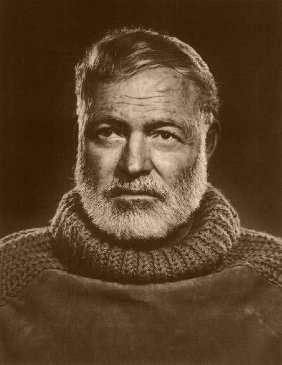

Nearly fifty years after his death, Ernest Hemingway remains a commanding presence in the literary world. His works annually sell well into the seven figures, and several of his astounding 27 books and 50+ short stories are considered to be masterpieces of American literature. Even the finest works of fiction pale in comparison, however, to Papa Hemingway’s real life. His exploits are legendary: winner of both the Pulitzer and Nobel Prizes, Bronze Star recipient, world class sports fisherman, big game hunter, boxer, bullfighting aficionado, war correspondent…the list goes on. Leaving the criticism of his literature for the pros, let’s instead take a look at the amazing life of the man himself.“Never confuse movement with action.”-Ernest Hemingway

It should be noted that Hemingway was at times neither a gentleman, a good father, nor a proper example of manhood, and no effort will be made here to rewrite history. Yet for all his flaws he represents an enigma of masculinity that so easily captures the imagination. His life was filled with the grand adventures that fill the dreams of many young boys and grown men alike.

Hemingway the Sportsman

As an accomplished outdoorsman, Hemingway was equally at home both stalking a lion through Africa’s long grass and cruising the Gulf Stream in search of marlin and tuna. Hemingway had learned how to handle a gun at a young age and was an accomplished hunter. His interest in the sport varied between pheasant and duck shooting out West to big game safaris in East Africa. It was in Africa that Hemingway hunted with P.H. Percival, a guide who had also hunted with another legendary sportsman, none other than Teddy Roosevelt. Hemingway’s love for safari was very clear in his uncontainable excitement in planning his second major hunt in 1954:During this second safari Hemingway became quite the professional hunter. The local game warden even left him temporarily in charge of the district he was quartered in, commissioning him an honorary game ranger. Hemingway loved the post and spent most of his days sorting out problem lions and elephants at the request of the local farmers.“Going back to Africa after all this time, there’s the excitement of a first adventure. I love Africa and I feel it’s another home, and any time a man can feel that, not counting where he’s born, is where he’s meant to go.”-Papa Hemingway

Yet while Hemingway loved hunting, it was when he had a rod in his hand that he was truly successful. It was from the deck of the Pilar that Hemingway famously landed the largest marlin caught to date in 1935, weighing an astonishing 1175 lbs. Truly, his greatest exploit by his own reckoning may very well not have been his literary achievements, but his success with rod and reel. In an interview several years ago, Hemingway’s son recalled that his father’s happiest days were always those spent aboard the boat he made with his own hands, chugging along the Gulf Stream in search of marlin. During his years spent in the Caribbean, he managed to win every single organized fishing contest put on in Key West, Bimini, and Havana, much to the chagrin of the locals.

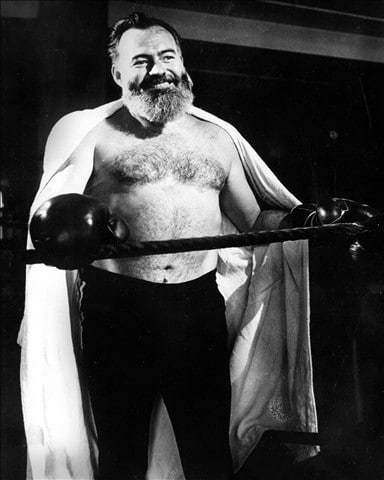

Hemingway the Boxer

Hemingway had practiced the sweet science since childhood and at one point was a successful amateur boxer. Following one of his victories in a fishing tournament in Bimini, the locals who had participated became angered at his ability to better fish waters they had fished their entire lives. Seeing an opportunity to combine his passions, he offered the locals a chance to win back their lost money. The terms were simple…go toe to toe with old Papa in the ring for three rounds and win, and the money would be theirs. The first challenger, a man who locals claimed could “carry a piano on his head,” made it only a minute and a half before the 35 year old Hemingway put him on the deck. The next three challengers suffered a similar fate, and Ernest went home with his prize money.-Hemingway in a conversation with Josephine Herbst

Hemingway’s love for boxing was unmatched by his other passions, and he even had a boxing ring built in the backyard of his Key West home, right next to the pool, so that he could spar with guests. Hemingway often dedicated his time not spent writing in Key West to boxing, even refereeing matches at the local arena. In one instance, he was presiding over a match where one fighter was being brutalized by the other. Every time the fighter would get knocked down, however, he would rise again to take more of a beating. Weary of seeing his fighter being abused so, the fighter’s manager, “Shine” Forbes, threw in the towel. Imagine his surprise when the ref picked up the towel and threw it out of the ring! Shine tried two more times to concede the match by throwing in the towel, and on the final try the ref threw it back in his face, which sent Shine over the edge. He climbed through the ropes and took a punch at the ref, effectively bringing an end to the match. Later that evening he was informed that the ref he had thrown a punch at was none other than Ernest Hemingway, local legend and internationally famous author. Embarrassed, Shine went to Hemingway’s home to apologize and was greeted by a smiling Hemingway who, not bothered by the punch thrown at him, had Shine and his friends come in for some sparring in his personal ring. Forging a friendship with the man, Hemingway even had Shine and friends spar for his friends’ entertainment at parties, and would pass a hat around afterwards to collect money for the young fighters.

Hemingway’s love of the sport carried over into the literary world as well. He was known for using boxing analogies in interviews, as well as for attempting to teach the poet Ezra Pound to box during his years in Paris. Several of his short stories reflect his love for the sport, including short stories Fifty Grand and The Battler, and the novel The Sun Also Rises.

Hemingway the Storyteller

It’s no secret that Hemingway could weave a masterful tale behind a typewriter, a fact that is reinforced by a glowing review of Across the River and into the Trees in the New York Times Book Review that labeled him “the most important author since Shakespeare.” But Hemingway was not just a good storyteller on paper. The tales he spun for friends and family captivated everyone within earshot, and were frequently so grand and full of wild incidents that those who listened were often left questioning whether one man could really have experienced so much in a single lifetime. Indeed, many of his tales seemed to stretch the truth, often more than a little. And yet, as his close friend and biographer A.E. Hotchner wrote, he so convincingly imparted his adventures that even the most outrageous yarn seemed feasible. He once recounted a tale to Hotchner as they sat down in an old Paris bar Hemingway frequented:In Hemingway’s biography, Hotchner accepts this and other tales without question, noting that every time he questioned the truth of such a tale, Hemingway would somehow produce photographs or other corroborating evidence to support his claims.“Back in the old days this was one of the few good, solid bars, and there was an ex-pug who used to come in with a pet lion. He’d stand at the bar here and the lion would stand here beside him. He was a very nice lion with good manners – no growls or roars – but, as lions will, he occasionally shit on the floor. This, of course, had a rather adverse effect on the trade and, as politely as he could, Harry asked the ex-pug not to bring the lion around anymore. But the next day the pug was back with the lion, lion dropped another load, drinkers dispersed, Harry again made the request. The third day, same thing. Realizing it was do or die for poor Harry’s business, this time when the lion let go, I went over, picked up the pug, who had been a welterweight, carried him outside and threw him in the street. Then I came back and grabbed the lion’s mane and hustled him out of here. Out on the sidewalk, the lion gave me a look, but he went quietly.” -Papa Hemingway

Hemingway the Nazi Submarine Hunter

Yes, you read that right. For nearly a year during World War II, Ernest Hemingway converted his 38 foot fishing boat Pilar into a Nazi submarine hunting ship in disguise. Coordinating with the Havana branch of the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, Hemingway loaded the Pilar down with heavy artillery and small arms alike, all the while maintaining the outward appearance of a standard fishing vessel. He filled the Pilar with friends interested in being a part of the mission, and they carried out daily patrols in the waters off Cuba. The goal was to look like a regular fishing vessel so that a Nazi sub would surface and attempt to board them. The U.S. navy regularly used such tactics, the vessels being known as Q-Ships, in an attempt to draw Nazi subs to the surface. Once a sub surfaced, the Q-Ships would quickly unveil their hidden firepower and hopefully sink the sub. Eventually the FBI took over Caribbean counter-espionage, and while the Pilar and her crew never fired on an enemy sub, it was adventure of the highest sort nonetheless.Hemingway the War Hero

As a young man, Hemingway served with the Red Cross on the Italian Front in World War I. Originally, he had sought to enlist in the Army, but poor eyesight barred his admittance, leading him to take a position with the Red Cross as an ambulance driver instead. Not long after arriving at the Italian Front Hemingway was seriously wounded. While delivering chocolates and cigarettes to soldiers on the line, he was hit by trench mortar fire, leaving over two hundred shrapnel fragments in his leg and nearly destroying his knee. Despite this gruesome injury, Hemingway managed to drag another injured soldier to safety, having stuffed the cigarettes he was carrying into his own wounds to temporarily stop the bleeding. Hemingway was to receive the Silver Medal of Military Valor from the Italian government for his courageous actions that day.Much later in life, following his exploits as a Nazi submarine hunter, Hemingway left again for Europe to see the action of World War II as a war correspondent. No stranger to action, Hemingway joined the Royal Air Force on bombing raids and followed infantry divisions around Europe wherever the fighting was heaviest. He witnessed the D-Day invasion from a landing craft just offshore and recorded many of the horrors of the war. Hemingway went on to take a much more active role in the combat he was there to document, often assuming the role of soldier himself in direct violation of the Geneva Convention’s guidelines for war correspondents. He once charged up to a cellar known to be filled with German SS, and tossing in a grenade, threw aside his non-combatant designation for the remainder of the war. In the chaos of war, Hemingway allegedly went on to form his own unit, which inexplicably had twice the firepower and alcohol rations of all other units, no doubt Papa’s doing. According to Hemingway himself, he and his unit were the first to enter the city during the Liberation of Paris, when he and his unit retook the Ritz Hotel, and more importantly the Ritz Bar, from Nazi control a full day before the Allied liberation force entered the city! An investigation into his actions during the war by the Army later charged him with several violations of his non-combatant status, including actions such as stripping off his non-combatant insignia and posing as a colonel in order to lead a French resistance group into battle. He was also accused of keeping a virtual armory in his private room, including anti-tank grenades and German bazookas. Hemingway responded to the allegations by noting that any titles given to him by the men were simply signs of affection.

As for the weapons in his room, he claimed he kept them “only for the troop’s convenience.” Several high ranking friends testified on his behalf, and at the end of the investigation he was not only cleared of all charges, but was awarded the Bronze Star for Bravery as a war correspondent. Colonel “Buck” Lanham, a close friend and later a Major General, noted:“After all, anyone who owned a ship in New England was automatically a captain, and all those from Kentucky were colonels from birth.”

“He is without question one of the most courageous men I have ever known. Fear was a stranger to him.”

Hemingway the Survivor

“Man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed but not defeated.”Perhaps most unbelievable of all Hemingway’s exploits was the sheer number of potentially fatal diseases and accidents he survived. Aside from the remnants of fragment in his leg left over from the World War I mortar hit, he also bore a bullet wound in his leg. This was the result of a self inflicted gunshot, an accident that occurred while trying to finish off a still thrashing shark he had dragged aboard while shark hunting. While shooting yourself in the leg is by no means the most glamorous thing a man can do, if you must do it, it seems best to do it while shark hunting. Hemingway’s more severe injuries and ailments came later in life. In his later years he survived anthrax, malaria, pneumonia, dysentery, skin cancer, hepatitis, anemia, diabetes, high blood pressure, and several major injuries.

-The Old Man and the Sea

During his last safari in East Africa, he survived not one, but two plane crashes. News of the first crash, deep in the jungles of Uganda, set off reports of his death back home, spawning numerous obituaries which Hemingway would later read daily over his morning coffee with amusement. Following the crash he, his wife, and the pilot were forced to camp overnight in the middle of elephant country, a survival story in itself. The second crash, following just several days after the first, was much more severe, and Hemingway was severely injured as a result. The pilot had been forced to perform an emergency dive to avoid a bird strike, and the plane ground-looped, eventually crashing. The plane burst into flames upon impact, forcing Hemingway to shoulder the door open and help his wife and the pilot to safety. He emerged with a laundry list of injuries, including first degree burns, internal bleeding, ruptured kidney, ruptured spleen, ruptured liver, a crushed vertebra and a fractured skull. Quite the ordeal, yet Hemingway managed a smile for the reporters waiting at his evacuation point, saying to them “my luck, she’s running very good.” Perhaps a bit of an understatement. Not a month later Hemingway was back in action, this time receiving second degree burns on his left hand and face while fighting a wildfire. All this and he lived to tell the tale.

Hemingway the Legend

Hemingway’s life experiences provided the source material for his literary works, and much of his life can be seen reflected in his fiction. The male protagonists in so many of his stories share both his machismo and his hidden pains, yet always exhibited grace under pressure. As he himself said:Critics during and after his lifetime tried to paint Hemingway as overly macho, claiming that his public persona was merely an act. Through reading his works and the biographies written about him by close friends, it becomes clear that Ernest Hemingway was not acting. He was, in fact, one of the most genuine men who ever lived. He lived life as he wished, never missing opportunities and never forsaking his passions. Perhaps he is best summed up by actress Marlene Dietrich, a close friend, who commented on his life to his biographer:“In going where you have to go, and doing what you have to do, and seeing what you have to see, you dull and blunt the instrument you write with. But I would rather have it bent and dulled and know I had to put it on the grindstone again and hammer it into shape and put a whetstone to it, and know that I had something to write about, than to have it bright and shining and nothing to say, or smooth and well oiled in the closet, but unused.”-Preface to The First Forty-Nine Stories

Sources:“I suppose the most remarkable thing about Ernest is that he has found time to do the things most men only dream about. He has had the courage, the initiative, the time, the enjoyment to travel, to digest it all, to write, to create it, in a sense. There is in him a sort of quiet rotation of seasons, with each of them passing overland and then going underground and re-emerging in a kind of rhythm, refreshed and full of renewed vigor.”

A. E. Hotchner Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir

A&E American Author’s Series Ernest Hemingway: Wrestling with Life